The Municipal Role in Accelerating Implementation of Renewable Energy

Purpose and Objectives

The purpose of this section is to help municipalities understand their sphere of influence in supporting RE development in their community. By the end of this section, you should be able to:

Articulate the significance of a ‘comprehensive’ vs. a ‘minimalist’ approach by municipal government to accelerating implementation of renewable energy

Distinguish across different roles that a municipality can play to accelerate implementation of renewable energy

Identify and build upon exemplary cases from municipalities across Canada to support strategic planning and action planning in your own municipality

Background and Significance

The best way to prepare for the future is to help shape it. Community energy planning is a tool to do just that. The push for decarbonization in Canada’s energy system is driving rapid social and technological innovation in the energy sector. Energy production technologies are increasingly decentralized and embedded themselves into local landscapes (e.g., solar panels, wind turbines, and district heating systems), while energy consumption is increasingly reliant on electricity infrastructure (e.g., electric vehicles; electric heat pumps) and renewable fuels (e.g., biomass-fueled heating systems). This is happening alongside an emerging ‘sharing economy’, such as ride sharing and bike sharing programs, that will result in fundamental change to how, where, and by whom energy is consumed in communities. Furthermore, new financial mechanisms are raising new possibilities for ownership and benefits-sharing of energy infrastructure (e.g., green bonds; property assessed energy retrofits; virtual net metering). Community energy planning (CEP) aims to minimize the impacts and maximize the benefits of these structural changes in our towns and cities and neighbourhoods.

Community energy planning is a socially inclusive process to identify and follow pathways for change in the way energy is produced, distributed, and consumed to meet community priorities for environmental and social sustainability. It sets targets for reducing energy-related environmental impacts and energy costs, along with clear actions for how a community, working with and through local government, will achieve those targets. The emphasis of that definition – with and through local government – is to suggest a leadership role for municipalities that is flexible, adaptive, collaborative, and facilitative. In other words, we are not talking about ‘from local government’. The socially inclusive and network-based approach of CEP is what distinguishes it from ‘Municipal Energy Plans’ or ‘Local Energy Plans’, which tend to be top-down and technocratic in their design and implementation and tend to focus on actions within the municipality as a corporation.

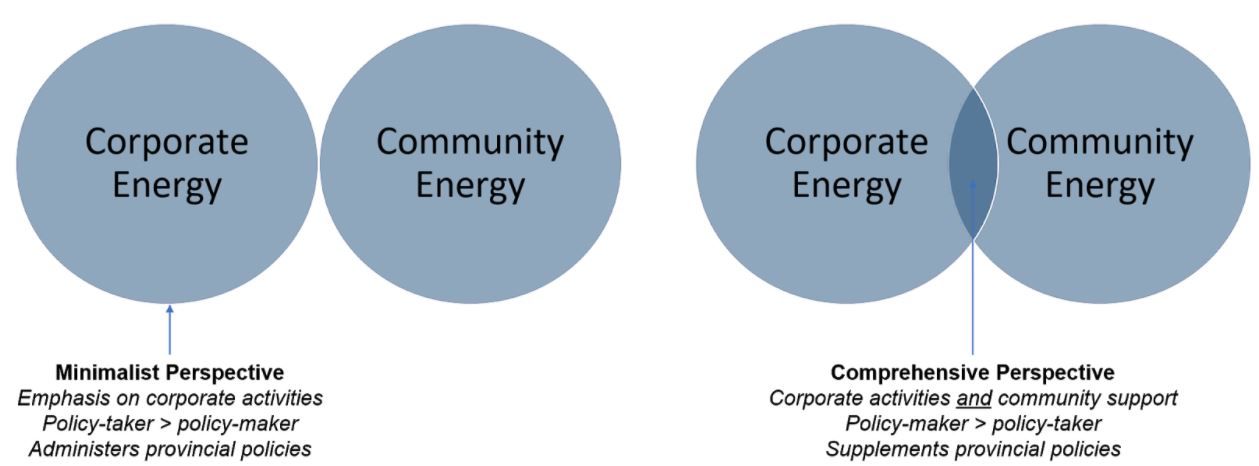

It is helpful to think about two distinct perspectives on the role of local government in implementing community energy plans. The first is what we might call a ‘minimalist’ perspective (see Figure below). From this perspective, the role of the municipality is limited to what it can directly control, and emphasis is placed on its own corporate operations and service provision functions such as waste collection, transit, and utilities. A minimalist perspective would focus the attention of the municipality on corporate energy, with limited if any proactive engagement in community initiatives. This view is more likely to understand municipalities as ‘policy-takers’, functioning as a unit of provincial administration. The second perspective is what we might call a ‘comprehensive perspective’ (see Figure below). From this perspective, the municipality also leverages its indirect influence and its capacity over community development more broadly. From this view, municipalities are more likely to become ‘policy-makers’ to the extent that political, financial, and regulatory constraints allow.

Actions emphasized under a minimalist purview are critical. Corporate actions lead-by-example and can help grow the market for renewable energy. And municipal service provision is certainly one primary pathway of direct influence for a municipality to help support renewable energy development. At the same time, municipalities, as a corporate entity, represent a very small proportion of the opportunities for emissions reductions and community benefits that can be achieved through renewable energy development. Further, the barriers to adoption of renewable energy eventually trace back to indirect levers of municipal influence: e.g., land-use planning, development controls, environmental protections, and social license, to name a few. As such, accelerating implementation of renewable energy is only possible when municipalities adopt a comprehensive perspective. Municipal Councils and staff understand this, and at the very least are sympathetic to the comprehensive perspective. The challenge they face is in operationalizing this perspective: what would a comprehensive approach look like?

Research

Figure 2 below provides a framework for thinking about what a comprehensive approach would look like. This typology is based on insights from governance theory and administrative theory, along with practical experiences described in the international body of literature on community energy planning and local energy management. On the left of the continuum, the role taken by a municipality involves direct market participation: i.e., the municipality is considered an ‘implementer’, which largely falls under the purview of corporate energy management. As we move to the right of the continuum, the role shifts to ‘facilitator’: i.e., the municipality leverages its resources, authority, and influence to drive projects and programs throughout the community, beyond its corporate sphere. The roles identified here are not mutually exclusive, meaning that a single program might require a municipality to play multiple roles. For example, the green standard program in Toronto, Ontario (described below) would fall under “Regulate” (setting a standard to which developers must comply in order to receive permission to proceed) as well as “Invest” (an indirect investment by forgoing revenue through reduced development charges, which incentivizes developers to exceed the standard).

Figure 2: A typology of the roles of local government in accelerating implementation of RE

Below, you can find examples and case studies of municipal actions that fall under each of these categories. The resources provided below are entry points into these ideas. Think of this as a warehouse of innovative policies and programs through which we are trying to speed up the process of policy diffusion. To compile these case studies, we undertook an extensive review of publicly available documents combined with targeted informational interviews with key stakeholders. The list of case-studies below can serve as a sort of ‘menu’ of options for practitioners to define the role of their municipality relative to their targets and / or ongoing programs. We also provide detailed information that can be used to support your own program design, and as evidence with which to make a compelling case to your Executives and Councilors.

Municipality as Implementer

Markham District Energy, Markham Ontario

Another example of this model is Énergie Kapuskasing Energy, which focused on rooftop solar during Ontario’s feed-in-tariff program.

Downtown District Heating System, Prince George, B.C

For more examples of bioheating systems across Canada, see here. The following examples are notable:

Rooftop solar on municipally owned property

Municipality as Investor

Shepard Landfill Solar Project

Toronto District Heating Corporation / Enwave

The City of Toronto invested in TDHC when it was privatized in 1998. The TDHC was renamed to Enwave in 1998 and built the Deep Lake Water Cooling System in 2004 to provide cooling to large buildings in the downtown core through a close-looped system that exchanges heat with cold water that is drawn from over 270 feet below the surface of Lake Ontario. The City sold its 43% stake in 2012 and Enwave is now owned by Brookfield Asset Management who is currently expanding the deep lake system.

Municipality as Regulator

City of Toronto Green Standard (see also the Town of Whitby Green Standard)

- Buildings are designed to accommodate connections to solar PV or solar thermal

- Design on-site renewable energy systems to supply a minimum of 5% of the building’s total energy load from solar PV, solar thermal or wind, or 20% from geo-exchange

Saint John Green Energy Zoning By-law Amendments

City of Vancouver – Zero Emissions Building Plan

Local Improvement Charges / Property Assessed Clean Energy

Norfolk County Rooftop Solar Building Permit Streamlining

Municipality as Encourager

Halifax Regional Municipality Environmental Performance Officers – Clean Energy Specialists

Halifax Regional Municipality has established two new positions with a core responsibility to “design and deliver clean energy programs and projects for the organization and the community”. The overall objective is to support implementation of their regional climate strategy that incorporates mitigation and adaptation targets. In theory, these positions will enhance institutional capacity to encourage and catalyze the implementation of renewable energy.

Town of Okotoks Master Development Plan

Okotoks is a leader in net zero carbon energy and encourages innovative solutions to carbon energy consumption in building design, energy sources. We develop partnerships to deliver renewable energy and all our energy comes from non-polluting, renewable sources. We eliminate fuel poverty while sharing information on energy education programs for individuals, companies, and institutions. -Town of Okotoks, Draft MDP

Regional Municipality of Durham Strategic Plan

Public-facing energy mapping tools

In our section on resource assessments, we provide examples of energy mapping activities that can raise awareness and support implementation planning. Another example comes from Google’s Project Sunroof which is making its way to the Canadian market in a partnership with MyHEAT. Another strong example is from a company called Mapdwell which has mapped rooftop solar potential across many cities, including New York City. These tools are primarily homeowner facing and are embedded into websites that connect homeowners with companies that offer site-assessments, project design, installation, and financing. These tools are also becoming detailed enough that they also serve prospective developers in identifying viable leads. A longer list of energy mapping tools developed by municipalities can be found here.

Key Takeaways

The specific role (action/level) pursued by a municipal government is dependent on a range of factors, all of which need to be considered before pursuing a particular line of implementation planning:

Administrative context, including their fiscal position and the authority granted to them by provincial governments

Political context, including the political leanings of Council and community as it relates to the role of local government broadly and the risk aversion of Councillors and the electorate relative to specific projects and initiatives.

Technology of interest, because each technology has a different set of opportunities and challenges which require different forms of support and steering

Governance context, to the extent that the role of a municipality should change in relation to the role of other key actors, such as utilities, other orders of government, community organizations, and so on.

Our research has revealed a wide range of levers/actions available to municipalities beyond municipal implementation of renewable energy. Many of these options – and especially those under ‘regulate’ – are relatively less resource-intensive in terms of financial resources and engage with a much larger set of opportunities. In separate sections, we will dig deeper into three of these actions: raising awareness and encouraging investments through resource assessments and public engagement; revising municipal land-use regulations; and drive project development through collaborative implementation.