Participatory Mapping for Actionable Community and Stakeholder Engagement

Purpose and Objectives

In the previous section on resource assessments, we addressed some of the technical challenges of incorporating renewable energy (RE) development into our local landscapes. In this section, we address some of the social and political challenges associated with RE development. The purpose of this section is to demonstrate how participatory mapping can help understand and address public opposition to RE development while improving collaborative implementation planning. By the end of this section, you will be familiar with:

The logic of participatory mapping as it applies to accelerating the implementation of RE

An innovative participatory mapping process for data-driven community and stakeholder engagement around local renewable energy development

Using outputs from participatory mapping to support policy decisions related to RE development

Background and Significance

The transition to RE is driving a profound transformation of our landscape. Wind turbines are an increasingly common sight in rural areas, altering the aesthetics of the landscape and introducing a new risk to bird and bat populations, while large fields of solar panels now cover fertile land that previously supplied food. Land and crops that once fed people are now feeding biofuel markets. These land-use trade-offs and landscape impacts are a primary driver of local opposition to RE projects. Opposition to RE is in many ways context-dependent, connected to landscape value systems and sense of place. In many cases, however, public opposition is not toward the RE infrastructure strictly speaking, but to the decision-making process and social relations through which that infrastructure came to be present on the landscape. In other words, social opposition is stronger when communities are not involved in the decision-making process, and when the benefits of development are limited to landowners and developers while the impacts are felt by the entire community.

At the same time, the likelihood that a project receives support from key implementation partners, including investors, developers, permitting authorities, and local utilities, is also dependent on a range of site-specific factors. Proximity to distribution infrastructure, zoning, and land-use are all factors that implementation partners might consider when deciding whether to pursue a particular project. In other words, implementation planning for RE development requires the same kind of proactive, place-based engagement.

Participatory mapping is an effective means through which to understand and address public opposition to RE development, while facilitating place-based collaborative implementation planning. Participatory mapping ensures that technologies and system designs are discussed in the context of the places and landscapes that matter to people. And it is a proactive approach, designed for meaningful engagement to inform local planning and policy, as opposed to opinion polls with little connection to policy development or townhalls held only after a project has already been proposed.

A Three-Phase Engagement Framework

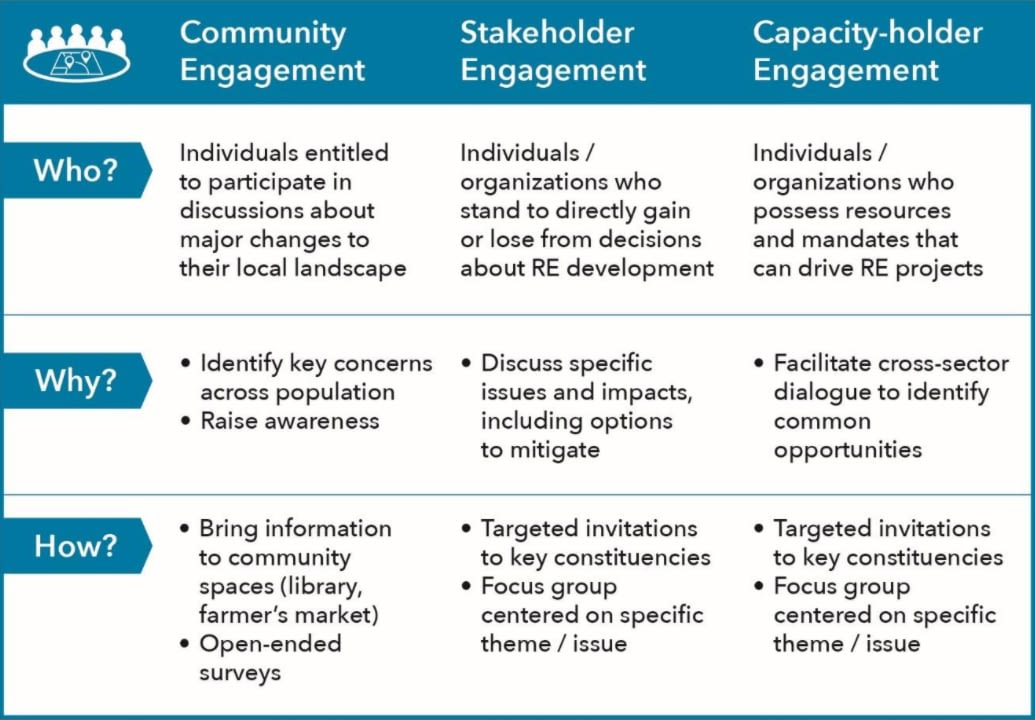

Figure 1: Our approach to engagement has three phases, described here.

In what follows, we will describe the broad contours of design at each phase. For guidelines to help you organize these activities in your own community, see this document.

Phase 1 - Community Engagement

Our approach to community engagement begins with a survey that assesses the level of support for RE, as well as general opinions and pervasive narratives about RE development. This link will take you to an example survey that you might deploy in your own community. This is meant only as an example – the design of the survey depends entirely on the outcome you’re interested in and on the social and political context in which it is being deployed.

In the table below we have summarized some key trade offs to consider when choosing between different survey delivery options, keeping in mind that these methods can be used in complementary ways. It is also important to note that the choice among the options depends on the nature of the research question, and the extent to which statistical representativeness and information gathering are valued over outreach and engagement. In-person delivery of the survey is strongly encouraged. Administering the survey in-person at various public spaces creates opportunities for shared learning and correcting common misperceptions about RE systems. Administering the survey in different public spaces at different times of the day helps to reach a broad cross-section of the population.

Table 1: Comparison of different survey delivery methods

| Method | Pros | Cons |

| In-person |

|

|

| Online |

|

|

| Phone |

|

|

| Key References |

|

|

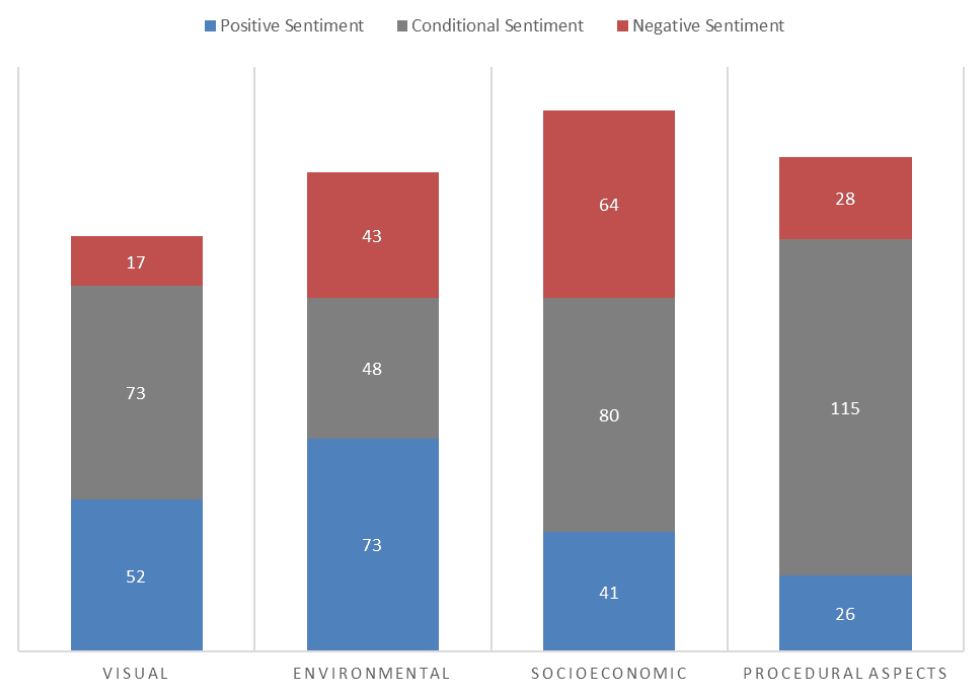

Opinions on RE technologies shared through the open-ended responses are best organized into key themes to help identify and prioritize common concerns. For this, we recommend the “VESPA framework”, a framework tested through recent academic research that organizes responses into four high-level themes: Visual aspects (e.g., landscape aesthetics), Environmental aspects (e.g., impacts on wildlife), Socioeconomic aspects (e.g., distribution of costs and benefits), and Procedural Aspects (e.g., transparency of the decision-making process). In addition to disaggregating data into more precise sub-themes, we advise coding responses according to sentiment, by distinguishing negative, positive, and conditional responses. These distinctions help to understand the nature of support vs. opposition, as well as the conditions under which individuals are likely to support or oppose a project. Indeed, our experience shows that most responses that might be considered ‘negative’ are in fact ‘conditional’ – i.e., they help to understand the nature of objection and mitigative options. The table and image below provide a snapshot of a typical output from this process.

Table 2: Example quotes to illustrate the coding protocol described above

| Visual Aspects | Environmental Aspects | Socioeconomic Aspects | Procedural Aspects | |

| Supportive | Their presence reminds me that we are making progress | Renewables are cleaner and less destructive than fossil fuels | They will bring jobs and investment | Renewables reflect the will of the people to produce clean energy |

| Opposed | They spoil the scenery, it’s too industrial | Renewables are damaging our local ecosystems | They are hurting my property value | Big investors are buying up our land and installing these systems before we even have a say |

| Qualified | I just don’t want to see too many turbines crowding one area | I think they’re fine as long as they are not located in the flyway of migrating birds | …if revenue comes back to the community somehow | I want to be more involved in the decision-making process |

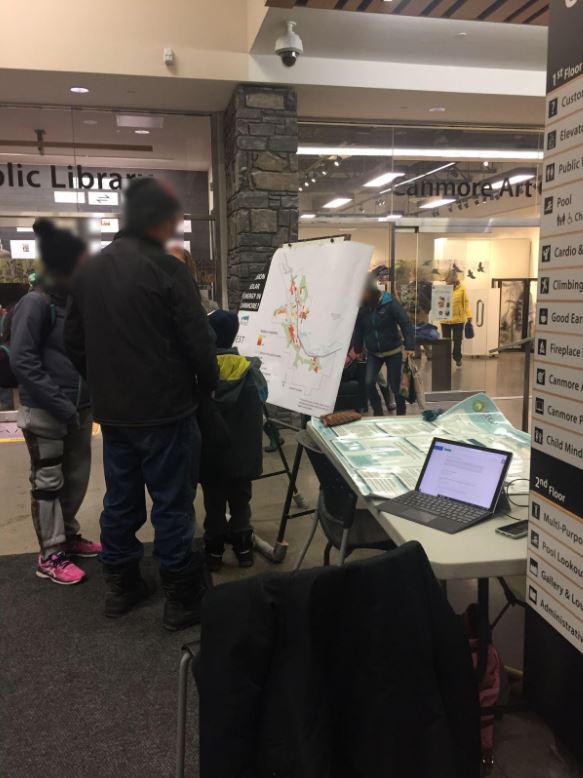

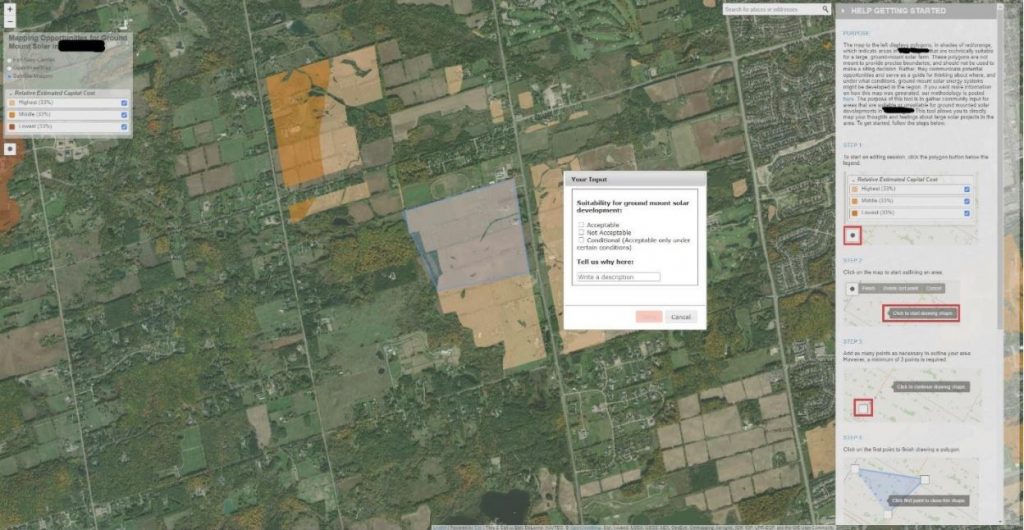

After completing the survey, participants undertake a participatory mapping exercise. In red, they indicated where they do not want to see new RE development; in green they indicate where they would accept or prefer to see new RE systems developed; and in orange they indicate where they would accept a development if conditions were met. Below, we are showing an example of what this looks like when participatory mapping is deployed for community engagement in-person and online.

Figure 2: A breakdown of the nature and sentiment of responses toward RE resources by frequency of occurrence

Figure 3: Participatory mapping for community engagement in-person

Figure 4: Participatory mapping for community engagement online

When coupled with the survey results, this spatial information helps us to understand how community sentiment around RE development is expressed spatially, in relation to specific places and landscapes across their community that are implicated in decisions to accelerate the implementation of renewable energy locally.

Phase 2 - Stakeholder Engagement

If community engagement helps us to achieve an understanding of the breadth of issues, stakeholder engagement helps us to understand issues at depth. In our experience, the key issues that require deeper conversation tend to implicate the following interest groups: farmers, naturalists / local environmentalists, and recreationalists. These groups have historically been at the ‘front lines’ of support and opposition to RE systems because their interests are directly tied to land, and RE systems are locally land-intensive. A comprehensive stakeholder mapping exercise is used to identify representative individuals and organizations who are invited to a focus-group style participatory mapping exercise. In a focus group, we foster peer-to-peer knowledge exchanges and dive into targeted conversations about specific impacts, ways in which they might be mitigated, and conditions under which RE projects might receive support from these interest groups.

The process of stakeholder engagement unfolds in two parts. First, participants are provided with a map output from a technical resource assessment. These maps can be customized to stimulate key policy conversations. With the farmer community, for example, we might map two scenarios that show RE potential with and without the inclusion of ‘prime agricultural land’ as a suitable land-cover. Indeed, the nature of the spatial information provided will depend on the nature of the conversation you are trying to elicit. In any case, participants at the focus group are given time to place indications on the map and answer a couple high-level questions (see here for an example), the responses to which can be organized using the VESPA framework described above. In this way, we gather individual thoughts before moving to the focus group which helps to ensure that individual voices are heard. Moving straight to the focus group runs the risk of having the input dominated by one or two strong personalities around the table.

Second, participants are asked to engage in a group discussion. The group discussion is best left unstructured and initiated with a discussion over any areas that seem to be trending toward consensus, either positive or negative. This helps the group understand their common ground. The discussion can unfold from there. As a facilitator, you will want to keep some probing questions in mind. The most effective probing questions fall along these lines: “what factors or issues are you considering as you add indications and markups to your map? Is it something about the specific location that is important to you, or about the general landscape features?”

In the end, two key datasets emerge from the exercise:

- written and verbal responses from key interest groups that represent general sentiment around key policy questions – e.g., agricultural land use or impacts on wildlife, as we mentioned above;

- a compilation of participant maps that can help provide some direction on how spatial plans and land-use regulations can be designed to help manage those policy issues

Phase 3 - Capacity-Holder Engagement

Capacity-holders are implementation partners for RE development. RE projects are only developed if/when individuals and organizations that hold ‘capacity’ facilitate them – e.g., if land-owners choose to convert their land directly or as part of a lease; if developers can secure financing to invest at a location; if the electric utility company enables connection; if planners zone accordingly; and so on. Bringing implementation partners into a room together helps to drive collaborative implementation planning. Engaging implementation partners separately, rather than as part of community and stakeholder engagement, reduces the chance that experts will dominate the conversation at a public meeting. And it ensures that implementation partners serve as an audience for the community and stakeholder mapping phases, and (ideally) act accordingly.

The process of capacity-holder engagement unfolds in two parts. First, participants are provided with a map output from a technical resource assessment. Similar to stakeholder engagement, these maps can be customized to stimulate key policy conversations. In our experience to date, implementation partners seem interested in the following spatial distinctions: public vs. private land; undeveloped industrial land; landfills that may be repurposed; prime agricultural land relative to sub-prime agricultural land; proximity to transmission infrastructure or distribution infrastructure. Indeed, the nature of the spatial information provided will depend on the nature of the conversation you are trying to elicit. In any case, participants at the focus group are given time to place indications on the map and answer a couple high-level questions (see here for an example), the responses to which can be organized using the VESPA framework described above. In this way, we gather individual thoughts before moving to the focus group which helps to ensure that individual voices are heard. Moving straight to the focus group runs the risk of having the input dominated by one or two strong personalities around the table.

Second, participants are asked to engage in a group discussion. The group discussion is best left unstructured and initiated with a discussion over any areas that seem to be trending toward consensus, either positive or negative. This helps the group understand their common ground. The discussion can unfold from there. As a facilitator, you will want to keep some probing questions in mind. The most effective probing questions fall along these lines: “what factors or issues are you considering as you add indications and markups to your map? Is it something about the specific location that is important to you, or about the general landscape features?”

In the end, two key datasets emerge from the exercise:

- written and verbal responses from implementation partners that share insights on barriers to implementation and opportunities for collaboration

- a compilation of participant maps that can help provide some indication of near-term development opportunities and insight into how spatial plans and land-use regulations can be designed to help realize those opportunities

Summary and Next Steps

The three-phase approach described above offers a framework through which to incorporate community and stakeholder voices into spatial and land-use planning processes related to RE development. In theory, the outputs from all phases of participatory mapping can be combined, to show high density of support or acceptance for a project. That said, these outputs do not provide answers – i.e., they are not meant as a siting tool, and do not in and of themselves decide about where the next RE system will be implemented. But they are a way to advance the conversation across communities and stakeholder groups, and they are crucial inputs into local land-use and energy planning.

Indeed, several policy and planning-level actions might be taken based on this information. Municipal staff may approach landowners in the area to discuss whether a RE project may be of interest. Indeed, most of the land that presents an opportunity for RE development is currently owned by private interests. Early engagement and creative partnerships will be necessary to realize these opportunities. Municipal staff may also amend their zoning by-law to clarify the kinds of land-use types that may be eligible for large-scale RE development and to specify the conditions under which a project would be granted a permit to proceed. One example comes out of Saint John, New Brunswick – a case we describe in more detail in the Follow through on policy statements with substantive zoning by-law changes section. Perhaps more importantly, undertaking this three-fold engagement process can advance the level of dialogue across the public, key interest groups, and key implementation partners, laying the foundation for accelerated implementation of RE projects.

Complementary Resources

Natural Resources Canada, 2014. Stakeholder Engagement Guide with Worksheets from Stakeholder Communications and Engagement Guide for District Energy Systems.

Retrieved from: https://www.nrcan.gc.ca/sites/www.nrcan.gc.ca/files/energy/pdf/engagementguide_eng_12.pdf

Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) is a federal body committed to ensuring the country’s natural resources are developed sustainably and responsibly. This Stakeholder Engagement Guide with Worksheets is a practical resource for municipal staff looking to engage the public on district energy systems (although, lessons from this document can be applied to other energy scenarios). To provide relevant context, the document starts by providing the rationale for why a municipality may want to create an external public engagement strategy. Next, the five key steps in planning an external engagement strategy are outlined.

- Step 1 is focused on understanding the local context in which district energy would become part of. This includes local considerations around leadership, capacity building, integration into existing planning and infrastructure, policies and regulations and the political environment.

- Step 2 involves identifying stakeholders and completing a stakeholder analysis to understand the nature of their interest in district energy as well as their level of influence.

- Step 3 guides the reader through a process to determine key messages and enhance those messages to address specific needs.

- Step 4 describes various public and stakeholder engagement channels, including mass versus targeted communication/engagement approaches.

- The final step illustrates how to create an integrated implementation plan based on the previous four steps.

One strength of this resource is the well-constructed appendix and worksheets which serve as practical tools for readers looking to design a municipal engagement strategy. At its core, AIRE is participatory and focused on understanding and incorporating community perspectives in the renewable energy planning process. This NRCAN resource can be a useful, practical guide for municipalities that want to undertake their own community engagement to inform projects.

Canadian Wind Energy Association (CanWEA). Wind Energy Development Best Practices for Indigenous and Public Engagement.

Retrieved on May 2019 from: https://canwea.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/canwea-bestpractices-engagement-May2019.pdf

The Canadian Wind Energy Association (CanWEA) is a not-for-profit association that facilitates and promotes responsible wind energy development. This guide outlines best practices for engaging with the public and Indigenous communities on the topic of wind power. Readers are able to access information related to every aspect of engagement. The resource starts by introducing the importance of community engagement and different aspects of the community that the proponent should be familiar with. Examples include economic conditions, the political landscape and demographic trends, among others. Protocols to establish and earn community support are outlined next. A section of the guide is devoted specifically to engagement with Indigenous peoples and includes important contextual information and considerations when working with these communities. Engagement and consultation activities are also discussed in a broader sense. This centres around 3 key elements: (1) creating opportunities for community members to attend meetings or receive information and provide feedback, (2) prepare and distribute jargon-free information about the project in multiple formats, and (3) responding to enquiries about the project. Tips for communicating with the media and putting on successful presentations are included to give readers practical ideas that they can incorporate into their own engagement work. Finally, best practices for addressing opposition viewpoints effectively and respectfully are described. A significant strength of this resource is that it is written in plain language which means it is accessible to a wider range of audiences. Checklists, templates and additional resources make it easy for the reader to apply best practices into their project. At its core, AIRE is participatory and focused on understanding and incorporating community perspectives in the renewable energy planning process. This CanWEA resource can be a useful, practical guide for municipalities or project proponents that want to undertake their own community engagement to inform projects.