La planification énergétique communautaire

De la planification à la mise en œuvreÀ propos de l’initiative

L'initiative de planification énergétique communautaire pour arriver à la mise en œuvre au Canada était un projet de trois ans qui s'est terminé en 2017.

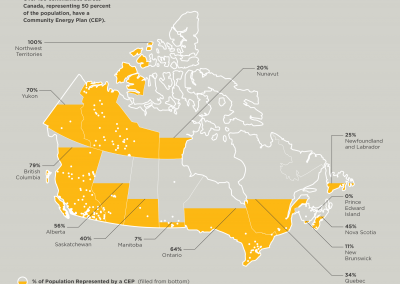

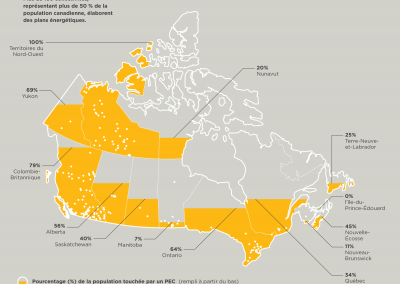

Les collectivités ont un rôle de premier plan à jouer dans le domaine de l’énergie. Partout au Canada ce sont plus de 200 collectivités, représentant plus de 50 pour cent de la population canadienne, qui élaborent des plans énergétiques en vue de définir leurs priorités en matière d’énergie. Or ces collectivités ont besoin d’aide pour réaliser et mettre en œuvre ces plans énergétiques.

La planification énergétique communautaire : de la planification à la mise en oeuvreest une initiative la Community Energy Association, de QUEST (Systèmes d’énergie de qualité pour les villes de demain), et L’institut pour l’Intélli Prospérité. Les objectifs principaux de cette initiative sont l’identification des outils nécessaires au développement de plans énergétiques communautaires (PEC) au Canada et à leur mise en oeuvre.

RESSOURCES

The resources developed from the Getting to Implementation Project are available here to help communities that currently have a Community Energy Plan navigate the challenges and get to implementation. They are also designed to help communities currently without a plan to design an integrated and principle-based community energy plan that optimizes the benefits and is poised for implementation.

Le cadre de mise en œuvre de l'énergie communautaire

RESSOURCES

The Community Energy Implementation Framework is a guide to help communities move community energy plans from a vision to implementation. It includes 10 strategies that provide insights, advice and a proposed path forward to foster widespread political, staff and stakeholder support, build staff and financial capacity, and embed energy into local plans, policies and processes to support implementation.

WHO MIGHT FIND THIS RESOURCE USEFUL?

Personnel du gouvernement local

Promoteurs immobiliers et gestionnaires d'immeubles

Élus au niveau local, provincial / territorial ou fédéral

Organisations non gouvernementales locales ou provinciales / territoriales

Distributeurs d'électricité, de gaz naturel et d'énergie thermique

Personnel provincial ou territorial

LE CADRE

Stratégie 1:

Stratégie 2:

Stratégie 3:

Stratégie 4:

Stratégie 5:

Le cadre de mise en œuvre de l'énergie communautaire

The Community Energy Implementation Framework is a guide intended to help communities move Community Energy Plans (CEPs) from a vision to implementation.

It includes 10 strategies that provide insights, advice and a proposed path forward to:

- Foster widespread political, staff and stakeholder support

- Build staff and financial capacity for implementation

- Embed energy into the plans, policies and processes of the local government

The Framework will answer questions such as:

- Who should lead the development and implementation of the CEP?

- What stakeholder groups should you engage with and when?

- How can you effectively communicate with various stakeholder groups to ensure meaningful engagement and input?

- What

internal and external resources are available to support CEP implementation? - How can local government staff incorporate energy into existing plans and policies?

- How can staff effectively monitor and report on implementation progress?

- And more!

What is Community Energy Planning?

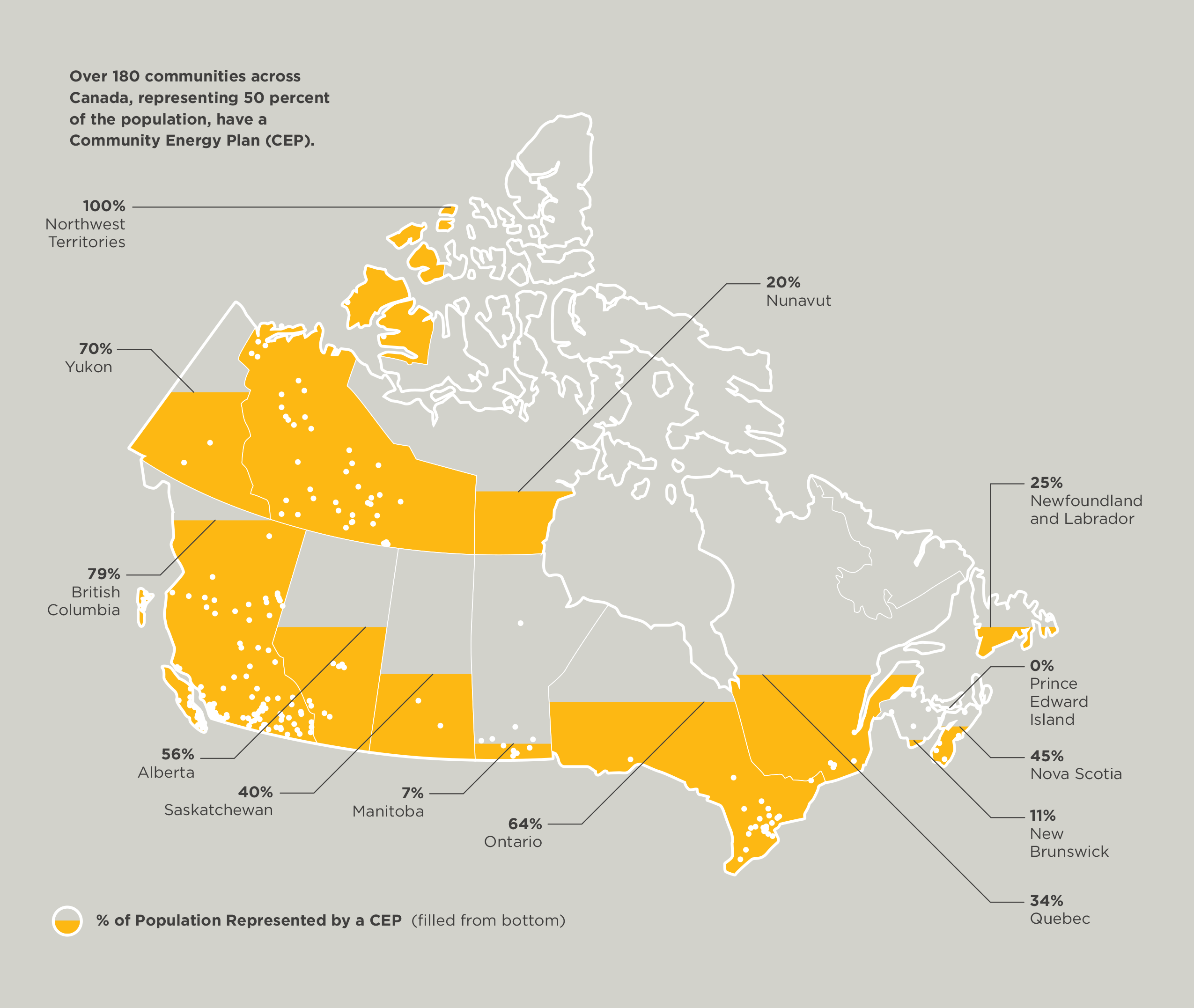

Across Canada, more than 200 communities,1 representing over 50

Figure 1: Community Energy Plans across Canada

A CEP defines community priorities around energy with a view to improving energy efficiency, cutting GHG emissions, achieving resilience and driving economic development. There is growing acceptance among all levels of government, energy distributors,3 the real estate sector and other stakeholders that CEPs provide a pathway for communities to become Smart Energy Communities. Smart Energy Communities:

- Integrate conventional energy networks (electricity, natural gas, district energy, and transportation fuel) to better match energy needs with the most efficient energy source

- Integrate land use

- Harness local energy opportunities

Smart Energy Communities can be characterized by six technical and six policy principles.

The Changing Landscape of Energy in Canadian Communities

Canadian communities have an important role to play in energy. They influence nearly 60

-

Figure 2: Energy End Use in Canadian Communities

-

Figure 3: Potential Increase in Energy Use in Communities across Canada

Figure 4: Local Government Influence on Energy

In addition to being one of the highest energy users per capita globally, Canadian communities have among some of the highest global energy costs per capita. Table 1 highlights average annual energy spending by businesses, households and governments in small, mid-sized and large Canadian communities. On average, a community of 100,000 can spend $400 million across the community on energy per year and much of that spending typically leaves the local economy.

Table 1: Annual Energy Spending in Small, Mid-sized and Large Communities11

| Community Size | Average Spending On Energy In The Community |

|---|---|

| Small Communities (less than 20,000 people) | Up to $80 million |

| Mid-sized Communities (20,000 – 100,000 people) | $40 million to $400 million |

| Large Communities (100,000 people to 2.5 million people) | $200 million to $10 billion |

Projected growth in energy consumption and the increasing costs associated with energy use are posing significant risks to Canadian communities, threatening to affect the quality of life of all Canadian residents and businesses.

Community energy planning can mitigate the risks associated with growing energy consumption and the inefficient use of energy in communities. Table 2 lists the many economic, environmental, health and resilience benefits of implementation.

Table 2: The Benefits of Community Energy Planning

| Bénéfices économiques | Avantages pour l'environnement |

|

|

| Health and Social benefits | Resilience benefits |

|

|

There are a number of emerging opportunities supporting an energy transition in Canadian communities such as:

- Climate policy: Ambitious international, national and provincial/territorial policies are emerging in favour of a more integrated approach to energy planning. The Paris Agreement signals an unprecedented multinational agreement to raise the bar on energy and climate change action.

- Supportive policies: L' Pan Canadian Framework on Climate Change presents opportunities for energy and climate action in Canadian communities. At a provincial and territorial

level there are over 640 policies, programs and regulations supporting community energy planning.13 - Urbanization: The preferences of Canadian homes and businesses are evolving. Today, 81

pour cent of Canadians live in urban regions, seeking improved connectivity between the places they live, work and play.14 Clean tech : There is a significant opportunity to capitalize on the globalclean tech market, which is expected to grow from $1 trillion in 2016 to $3 trillion by 2020.15

Currently, Canada’s share represents 1.3pour cent of the global market.16

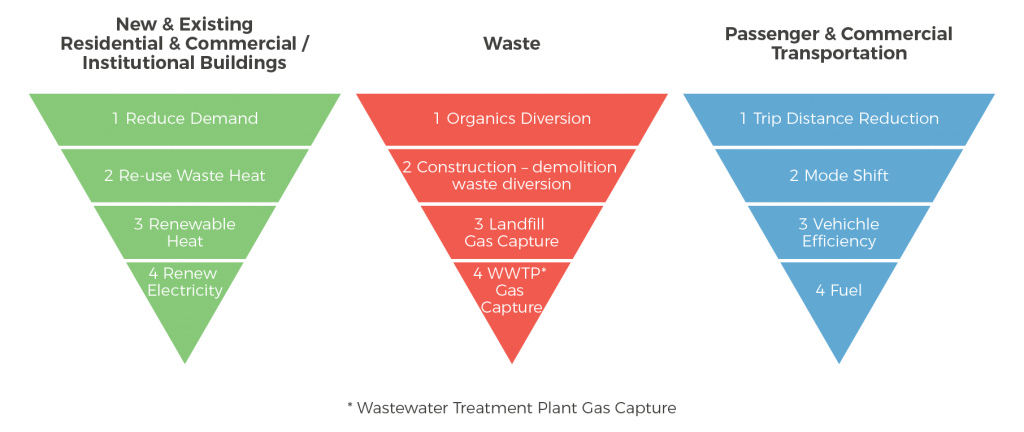

Approaches to Community Energy Planning

Traditionally, Canadian communities have planned for buildings, transportation, land use and waste in silos. The way in which communities are planned locks in energy and emissions impacts for decades. There is an untapped opportunity to integrate buildings, transportation, land use, waste and water systems to achieve greater energy efficiency, reduce GHG emissions and drive economic development.17

Over 200 communities across Canada, representing more than 50

CEPs are often led and implemented by local governments in partnership with a broad range of community stakeholders, including energy distribution companies, the real estate sector, the private sector, NGOs and provincial/territorial governments.

CEPs often vary from community to community,

- Community-wide energy and/or GHG emissions inventories

- Energy conservation and/or GHG reduction targets, and in some cases sub-sector targets for the building, waste and transportation sectors

- Proposed community-wide actions and strategies to meet the targets, including but not limited to, energy efficiency in buildings, planning and policy measures, transportation (including public transit, active transportation, low carbon vehicles and other transportation actions), waste, distributed energy resources (including renewable energy, district energy and combined heat and power), and water conservation

- Analyses of the economic, environmental, health and social benefits of implementation

- Key Performance Indicators to allow the community to monitor and report on

implementation

CEPs also vary with respect to the level of detail contained in energy inventories as well as how deeply the economic, environmental, health and social benefits of CEP implementation are analyzed.

Table 3 describes various approaches to CEP development as well as the resources required to develop and the type of information they provide. Communities should pursue an approach that aligns with the community’s priorities, size, demographics, and available resources.

Table 3: Approaches to Community Energy Planning19

| CEP Approach | Description | Community Size | Cost | Information Provided |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inventory | A community energy inventory is the first step in defining community needs around energy. | Any community size | $15,000-$20,000* |

|

| Get Started | Focusing on a specific project, initiative or opportunity can often be done expediently and economically and can help garner the support needed to develop a CEP. Consider the actions listed in Figure 6 (found under “Implement a Single Energy Project“) | Any community size | Project cost |

|

| Practical Tactics | Communities with energy and emissions inventories can develop projections and a year-by-year implementation plan. This approach may include frequent involvement of elected officials, staff, and stakeholders. These plans can be renewed frequently (e.g. every 3-5 years). | 50,000 or less | $5,000-$10,000** |

|

| Targeted Plan | Larger communities can develop more comprehensive and long-term plans. This typically includes more stakeholder consultations and detailed projections. These plans can be renewed every 5-7 years. | 100,000 or more | $50,000-$150,000 |

|

| Comprehensive Plan | Communities with greater resources can include more comprehensive analyses when developing their CEP, including a broader range of energy end uses (e.g. food production). | 250,000 or more | $100,000-$250,000 |

|

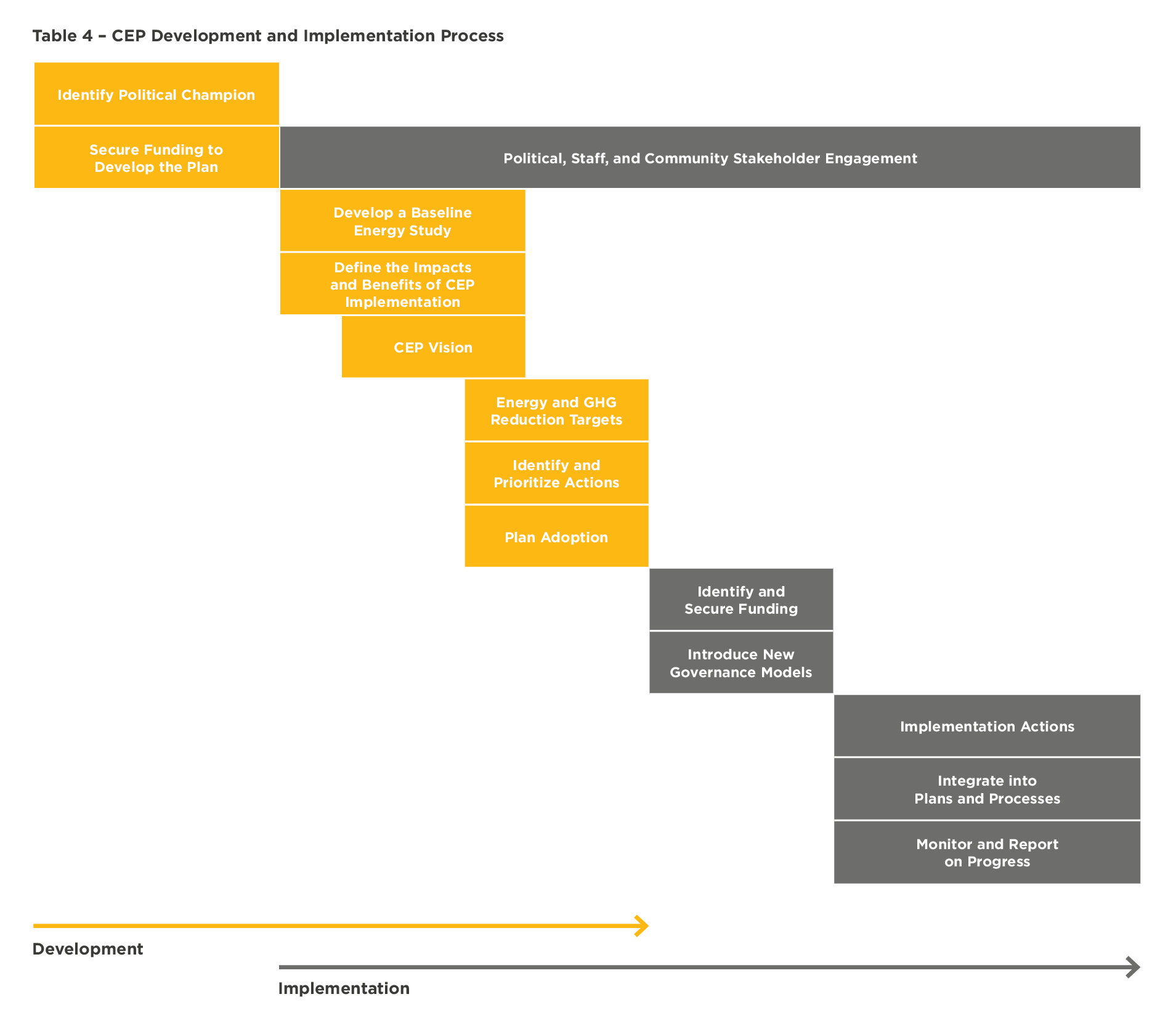

The process of implementing a CEP will differ from community to community and depends on a number of factors, ranging from the community

Table 4: CEP Development and Implementation Process*

Strategy 1

Develop a Compelling Rationale for Undertaking the Community Energy Plan

Community energy planning can help mitigate risks, and has the potential to lead to widespread economic, health, social, resilience and environmental benefits. While greenhouse gas (GHG) reductions are an important part of community energy planning, it is critical to define what other benefits the CEP can generate. A critical success factor for CEP implementation is defining how the CEP will enable the community to meet its economic, environmental, health, social and resilience objectives.

GTI Advice

- Focus on the widespread benefits of CEP implementation, beyond GHGs: CEPs have the potential to lead to significant economic, health, social, resilience and environmental benefits. Be sure to describe how CEP implementation will lead to measurable benefits when describing the plan to senior management and council

- Caution against analysis paralysis: The analysis to support a CEP should only go as deep as is needed to gain support from senior decision makers and elected officials

- Be precise, yet efficient: Aim for detailed, precise and

defendable data. Consider that projections beyond 30 years have inherent limits due to technology advances, fluctuating energy prices, changing business models and cultural attitudes - Focus on actions under the jurisdiction of local government: When developing models, include business-as-usual assumptions as well as provincial and federal policies that have already been adopted. Avoid including provincial, territorial or federal policies that have not yet been adopted

- Use familiar language: Use language that resonates with the stakeholder group you are engaging

Table 5: Analyzing the Widespread Benefits of CEPs

| Summary Of Benefits | What You Will Need | Resources To Get Started | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Benefits |

|

|

|

| Economic Benefits21 |

|

|

|

| Health and Social Benefits |

|

|

|

| Resilience Benefits |

|

|

|

Methods for Measuring the Economics of Community Energy Plans

Table 6 illustrates a range of methods for measuring the economic impacts of CEPs.26

Table 6: Measuring the Economics of Community Energy Plans

| Method | Purpose | Relevant CEP Approach* |

|---|---|---|

| Community Energy Cost | Discuss total community energy use in a metric everyone understands, in order to generate different conversations with elected officials and stakeholders. |

|

| Financial Feasibility | Screen and prioritize measures, programs, or portfolios to identify if the investment will break even. |

|

| Levelized unit energy cost | Compare the unit costs of different energy generating technologies across the expected lifetime of the asset, in real dollars per kWh. |

|

| Marginal Abatement Cost Curve | Compare GHG emission reduction options according to which will cost the least or deliver the most financial savings, and according to their potential impact on GHG reductions. |

|

| Community economic benefits | Inform the decision-making process, and stakeholders, on the total value to the local economy of a CEP, considering the how direct expenditures recirculate through local businesses, households, and tax revenue. |

|

| Screen and prioritize measures, programs, or portfolios to identify if benefits over time exceed initial |

|

Relevant Resources

Case Study 15: Net Zero Community in London, Ontario

West Five (www.west5.ca) is a 70 acre, mixed-use site located in London, Ontario. The site is being developed by Sifton Properties, in partnership with S2E Technologies. When completed, the neighbourhood will include 2,000 residential units, commercial and retail space, and parkland. The development will include a number of Smart Energy Community Principles,89 including energy efficient buildings (e.g. the use of enhanced insulation), the use of renewable energy resources (e.g. solar shingles) and matching land use needs and mobility options (e.g.

Read the Community Energy Knowledge Action Partnership case study ici.

Case Study 17: Monitoring and Reporting on CEP Implementation in the City of London, Ontario

The City of London Community Energy Action Plan (CEAP) was adopted in 2014. Alongside the plan, the City of London developed a background document describing a methodology for monitoring and reporting on community energy use. The background document describes a methodology for developing annual energy and emissions inventories. The document describes how the City of London will also work with stakeholders to develop new Key Performance Indicators, including economic, transportation, and energy performance indicators. The results from energy and emissions inventories, and other Key Performance Indicators will be included in an annual progress report outlining implementation progress of the CEAP.90

Strategy 2

Collaborate with a Political Champion and Engage Council

Council support is critical for implementation, as it provides direction, inspiration and impetus for local government staff, and the community, to prioritize community energy planning. Communities that take the time to engage with a political champion and council on an ongoing basis may be better positioned to move forward on implementation. Early engagement can help to surface key questions, considerations and possible challenges and can guide the CEP implementation team to focus on the aspects of the plan that matter most to the community.

Consider the following when engaging with political champions and elected officials, including when to engage them, why to engage them and how to engage them.

Collaborating with Political Champions

| Who to engage | When to engage them |

|

|

| Why engage them | How to engage them and what to focus on |

|

|

Building Widespread Support from Elected Officials

| Who to engage | When to engage them |

|

|

| Why engage them | How to engage them and what to focus on |

|

|

Relevant Resources

Case Study 2: Measuring the Widespread Economic Benefits in the City of London, Ontario

The City of London, Ontario has conducted an economic analysis to measure various economic impacts and potential benefits of implementing their Community Energy Action Plan (CEAP). The analyses, conducted in-house, demonstrate community-wide energy spending, the proportion of energy spending leaving the local economy and the potential to recirculate energy spending based on the implementation of their plan.

The approach

- Energy spending analysis

Video supporting energy spending analysis: Turning energy data into energy dollars- The City of London has also produced infographics based on the analyses, available here

Case Study 3: Measuring Green Jobs in Durham Region, Ontario

The Region of Durham Community Climate Change Local Action Plan highlights the estimated environmental, economic and social impacts of implementation. The plan is available

Case Study 4: Measuring the Impacts of Sustainable Communities on Local Retail Sales New York City, New York

The New York City Department of Transportation created a methodology for measuring the economic impacts of improved streetscapes and active transportation infrastructure on retail sales. The study is available here: New York City Department of Transportation (December 2013). The Economic Benefits of Sustainable Streets.

Case Study 5: Framing the Value Proposition, Edmonton, Alberta

There is a lesson to be learned in how Edmonton’s Sustainable Development Department communicated the need for the strategy. First, it was framed as a risk management strategy designed to protect Edmonton’s quality-of life from climate and energy risks. Secondly, it provided a compelling economic business case involving ten community-scale programs (for advancing energy conservation, energy efficiency and renewable energy uptake) that would deliver a net public benefit of $3.3 billion over 20 years.

Case Study 21: Integrated Financial Planning in the City of Coquitlam, British Columbia

Coquitlam’s award-winning integrated financial planning framework is comprised of three separate but complementary planning processes. These processes result in a set of integrated plans that support the overall vision and mission of the City and align activities and resources to achieve the strategic goals and annual business plan priorities set by Council.

- Council’s Strategic Plan – aspirational, future-looking plan, updated every four years following the municipal election. It articulates the vision, mission, values and broad strategic goals.

Progress of the plan is monitored through an annual review of key performance measures and accomplishments - Business Plan – translates the

high level strategic goals into annual business plan work items and priorities, established by Council. A set of performance measures are reviewed annually to monitorSuccès of the business plan - Financial Plan – provides the resourcing strategy to support the strategic and business plans. Updated annually, it is a five-year plan that includes both operating and capital components

Evaluation of achievements informs the next cycle of planning. For example, the City’s performance is reviewed every four months with a Trimester Report to Council. It includes an update on the progress of the work items under the Business Plan priorities and a review of operating and capital budget variances, labour vacancies, economic indicators including construction and development activities, and major spending during the trimester. The intent of the report is to view the City’s activities and progress balanced with the status of the City’s financial and human resources.

In this model, it is important that staff responsible for developing and implementing the CEP ensure that its goals and actions are reflected in Council’s (strategic) plan and that these goals and actions maintain a high profile throughout the budgeting/financial plan process.

See the Strategic Plan here: City of Coquitlam (2012). 2012-2015 Strategic Plan.

Strategy 3

Développer un modèle de gouvernance qui soutienne une transition énergétique communautaire

New governance models provide a platform for political, staff and community stakeholders to convene regularly. In some cases, they provide the legal framework needed to implement projects. This can ensure that a process is in place to monitor and report regularly on the implementation of the CEP.

GTI Advice

- Ensure that there is a clear purpose for new committees or governance structures

- Determine if the objective can be accomplished within existing committee structures or if a new structure should be introduced

- Consider that new, dedicated committees will ensure that the CEP remains at the forefront for elected officials, staff and community stakeholders

- Ensure that the governance structure involves all political, staff and community stakeholders in a constructive dialogue, and ensure they feel that their contribution is valued and supported

- Ensure that the CEP progress is monitored regularly and reported back to all stakeholders annually. See Strategy 8: Monitor and Report on CEP Implementation for more information

- Ensure that committee members, particularly those who are attending on a volunteer basis, are not overworked through the number of meetings or tasks

- There is no “one size fits all” solution for communities. Choose a structure that works for your community

Table 7 provides a list of governance models to consider to support implementation at the council, staff and stakeholder levels. The table below is non-exhaustive, and communities should consider implementing governance frameworks for each of the tiers involved in the CEP (council, staff and stakeholders).

Table 7: Governance Models to Support CEP Implementation

· A community-wide committee should be formed to maintain ongoing support for CEP implementation activities.

· The committee should meet on an ongoing basis.

· The committee can include a Council representative but this may be informal

· Staff may attend meetings as a resource but generally not be members

· Meeting minutes would not usually be reported to Council in a formal way

· Meetings would be open to the public, by nature of the committee

· See Strategy 7: Engage community stakeholders and recognize their implementation progress.

| Options | Primary Tasks and Considerations |

|

Committee of Council

Mayor’s Task Force

|

|

| STAFF-LEVEL | |

|

Dedicate Staff to Manage CEP Implementation

|

|

|

Staff Advisory Committee

|

|

|

Staff Committee

|

|

|

Corporate Energy Manager

|

|

|

Community Steering/Advisory Committee

|

|

Relevant Resources

- FCM – Passing Go: Moving Beyond the Plan

- Clarke, A., MacDonald, A. & Ordonez-Ponce, E. (forthcoming). Implementing Community Sustainability Strategies through Cross-Sector Partnerships: Value Creation for and by Businesses. In: Borland, H.,

Lindgreen , A., Vanhamme, J., Maon, F., Ambrosini, V. & Palacios Florencio, B. Business Strategies for Sustainability: A Research Anthology. London, UK: Routledge.(View pre-publication version) - Clarke, A. & Ordonez-Ponce, E. (2017). City Scale: Cross-Sector Partnerships for Implementing Local Climate Mitigation Plans. Climate Change and Public Administration. Public Administration Review.

Case Study 6: Establishing a Committee of Council in Yellowknife, Northwest Territories

The Community Energy Planning Committee was established by City Council on September 10, 2007, following the completion of the Community Energy Plan (CEP).79 The Committee is chaired by the Mayor and includes representatives from across the Community. The primary purpose of the Committee is to assist the City of Yellowknife in an advisory capacity to ensure the CEP is implemented and evolves in an effective manner. The scope of the Committee is to report and make recommendations to City Council through the appropriate

Case Study 7: Establishing a Governance Framework for Edmonton’s Community Energy Transition Strategy, Edmonton, Alberta

Edmonton City Council formed an Energy Transition Advisory Committee.81 Committee members serve

Case Study 8: Stakeholder Engagement in the City of Kelowna, British Columbia

In 2012, the City of Kelowna adopted a Community Climate Action Plan containing 87 actions to be implemented by 2020. Of those actions, 59 were assigned to the local government and 28 were assigned to community stakeholders, including utilities, provincial government and others. In an effort to ensure that community stakeholders understood their roles in the implementation of the plan, the City of Kelowna circulated letters to the organizations responsible for implementing actions in the plan. These letters enabled the City of Kelowna to move forward on implementing actions that are not within its jurisdiction.82

Case Study 9: Stakeholder Engagement in Markham, Ontario

In 2014, the City of Markham began to develop a Municipal Energy Plan (MEP). As part of the MEP, the City created a Stakeholder Working Group.83

The desired outcome of the Stakeholder Working Group is to provide recommendations and feedback on the development of Markham’s MEP including:

- Identifying energy opportunities and solutions to increase local energy production and conservation

- Identifying synergies between industry stakeholders to implement MEP recommendations

See the Municipal Energy Plan Stakeholder Working Group Terms of Reference ici.

See the list of stakeholders participating in the MEP Stakeholder Working Group ici.

Strategy 4

Determine which Department and Staff Person(s) will Oversee CEP Implementation.

The department in which a CEP sits can significantly impact implementation. For example, a CEP can be led by the planning, community development or the economic development department. CEPs may also be led by local NGOs or by the provincial/territorial government.

Consider the following questions:

- What department (or organization) should oversee the CEP?

- What

staff person should act as the lead for CEP development and implementation?

What Department (Or Organization) Should Oversee The CEP?

- Recognizing that collaboration and coordination among political, staff and community stakeholders is central for community energy planning, the department in which a CEP is housed should be well-positioned to communicate and liaise with political, staff and community stakeholders

- The department should be well-positioned to communicate the widespread economic, environmental, health, social and resilience benefits of CEP implementation.

- CEPs are often housed within the planning department due to the strong links that community energy holds with planning and development.

- Some communities house their CEP in the economic development department, recognizing the strong link between economic growth and community energy transition

- In some cases the following types of organizations may be well-suited to lead CEP development and implementation:

- A local NGO organization with a mandate related to community energy

- Regional government, if applicable

Territorial /provincial government, particularly for rural and remote communities

What Staff Person Should Act At The Lead For CEP Development And Implementation?

- The CEP will have significantly more

Succès if there is a dedicated staff person overseeing CEP development et de la implementation. Without a dedicated staff person, implementation often falls to the sides of many desks and eventually loses momentum. Assign a dedicated staff person to oversee implementation, such as a Community Energy Manager, Planner or an Economic Development Officer. The staff person should have adequate capacity to manage oversight of the CEP - A staff person that sits at a management level is often well-suited to oversee CEP development and implementation. A manager remains equally as close to senior management/council as it does to staff and stakeholders working to implement the plan on the ground. If this is not possible, try to appoint a staff person with the ability to communicate and liaise with political, staff and community stakeholders, and who possesses some of the knowledge, skills and academic credentials listed below

Skills and Credentials for CEP Implementation

Knowledge and Skills of the Designated Staff Person

- Communication

- Stakeholder and community engagement

- Project management and facilitation

- Research and writing

- Energy literacy

- Change management

- Leadership

- Strategic planning

- Familiarity with local government processes and legislation

- Policy and program development

- Sustainability practices

- Quantitative data analyses (spreadsheet software)

- Mapping (geographical information system software)

- Business case development

- Feasibility/financial analysis

Academic Credentials and Certifications32

- Degree in planning, public policy, engineering, sustainability, environmental science, resource management, business

- Degree, diploma or certificate in communication

- Registered Professional Planner / Member of the Canadian Institute of Planners

- Registered Professional Engineer

- Certified Community Energy Manager (CCEM)

- Certified Energy Manager (CEM)

- Registered Engineering Technologist

- LEED Professional Accreditation (LEED AP)

- Project Management Professional (PMP)

Consider Developing the CEP at a Different Scale.

While CEPs are often led by a local government, they do not have to be. CEPs can be developed at different scales, for example at a regional or neighbourhood scale. Developing a CEP at an alternative scale may be an effective approach for your community if:

- You are a small community with

little capacity to develop a CEP - You are a large community whereby a CEP may not be an effective way to meet the highly varying needs across the community

- You live within the jurisdiction of a regional government and can find efficiencies by coordinating among communities in the region

How to Get Started

- Reportez-vous à la Appendix IV – Provincial/Territorial Municipal Organizations that may have Community Energy Planning Resources. Many organizations across Canada provide community energy planning support and can connect communities with the resources or contacts needed to get started

- Consider reaching out to local government staff, regional government staff or neighbouring communities as well as local energy distributors, to begin discussions about possible models for community energy planning

- Consider that many local energy distributors or provincial/territorial governments provide or match funding to support the development and implementation of a CEP

- Consider risks associated with staff turnover and attrition. Many communities, and most often rural and remote communities, face high staff turnover. High staff turnover can lead to a fragmented implementation process and the loss of relationships and corporate knowledge with respect to implementation. In addition, all communities face the risk of losing corporate knowledge as a result of staff attrition

- Consider the approaches listed in Strategy 3: Develop a Governance Model that Supports a Community Energy Transition. The focus of this strategy is to embed the CEP within the processes of the local government and focus on building a network of champions, and redundancy in staff involvement in the CEP

- If possible, provide incentives to reduce staff turnover, such as:

- Provide professional development opportunities such as training programs

- Offer frequent formal and informal recognition and/or awards based on performance to improve employee morale and motivation

- Provide employee engagement opportunities to improve employee contentment and loyalty

- Sometimes, corporate knowledge may lie with a contractor that has been retained for community energy planning consulting services for the community. Consider engaging or re-engaging with former consultants if your community is facing a loss of internal corporate knowledge about previous efforts related to the CEP

Relevant Resources

Case Study 6: Establishing a Committee of Council in Yellowknife, Northwest Territories

The Community Energy Planning Committee was established by City Council on September 10, 2007, following the completion of the Community Energy Plan (CEP).79 The Committee is chaired by the Mayor and includes representatives from across the Community. The primary purpose of the Committee is to assist the City of Yellowknife in an advisory capacity to ensure the CEP is implemented and evolves in an effective manner. The scope of the Committee is to report and make recommendations to City Council through the appropriate

Case Study 7: Establishing a Governance Framework for Edmonton’s Community Energy Transition Strategy, Edmonton, Alberta

Edmonton City Council formed an Energy Transition Advisory Committee.81 Committee members serve

Case Study 16: Monitoring and Reporting on Implementation Progress in the City of Guelph, Ontario

CEP reporting is coordinated annually by the Community Energy division of the Business Development and Enterprise department, and presented to the Corporate Administration, Finance & Enterprise Committee (this Committee is appointed by Council and made up of Councillors). A dashboard is used to display progress within eight key activity categories, plus a description of the status for each individual activity.

See the Guelph Community Energy Plan ici.

Case Study 18: Efficiency One, Nova Scotia

Efficiency One in Nova Scotia, formerly Efficiency Nova Scotia, has provided on-site energy managers for organizations such as Cape Breton University, Capital District Health Authority, Dalhousie University and Nova Scotia Community College. These embedded energy managers help to identify and coordinate projects to achieve substantial energy efficiency savings. For example after first six months of the partnership between Efficiency One and Capital Health in 2012, several projects were initiated totalling savings of $118,000 per year.91

Case Study 19: Community Energy Planning Alternatives for Small Communities – Eco-Ouest

Eco-Ouest, led in partnership with CDEM, SSD, has developed a program designed to help provide expertise to smaller municipalities in Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta that face resource and capacity constraints for CEP development and implementation. Eco-Ouest has partnered with rural municipalities in each of these provinces to create energy and GHG emissions inventories and Climate Change Local Action Plans such as the inventory for the Rural Municipality of St. Clements and plans for the Rural Municipality of Saint-Laurent and Rural Municipality of Taché. CDEM also incorporates a regional perspective by comparing neighbouring communities’ energy and emissions performances and sharing successful projects and case studies.92CDEM. (n.d.). Eco-West. Retrieved from CDEM Website

Case Study 20: Yukon Energy Solutions Centre

The Yukon Energy Solutions Centre is part of the Energy branch in the Government of Yukon Department of Energy, Mines and Resources.

The Energy Solutions Centre offers community-level energy services to such as:

- Providing technical information and financial incentives to encourage the use of energy efficient appliances and heating systems at the local level

- Providing comprehensive energy planning services, including energy baseline assessments and policy reviews

- Providing training courses to build local technical capacity to implement community energy plans and projects

- Participating in outreach and public education on the health, safety, economic and environmental benefits of energy efficiency and renewable energy

To learn more about the Energy Solutions Centre visit http://www.energy.gov.yk.ca/about-the-energy-branch.html

Strategy 5

Engager le personnel à travers le gouvernement local. Identifier les champions du personnel et intégrer le PEC dans les descriptions de travail du personnel

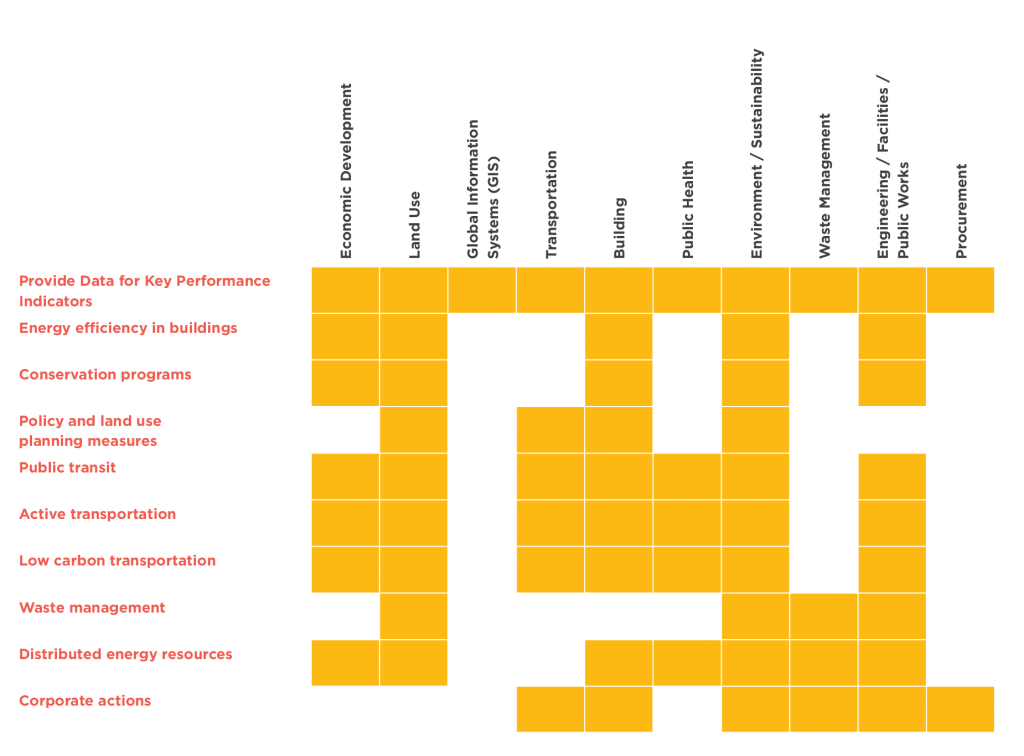

CEPs cross many departmental boundaries and consequently require early and ongoing inter-departmental coordination and collaboration. The following non-exhaustive list of local government departments should be involved in the development and implementation of the CEP.

- Aménagement du territoire

- les transports

- Economic development

- Finance

- Chief Administrative Officer

- Engineering/public works

- Public health

- Environment/sustainability

- Communications

- Global Information Systems

- Others as needed

Engagement should take place at the senior management and junior/intermediate staff level. Table 8 provides a snapshot of how some of the actions within a CEP relate to various departments. This is intended to act as a starting point for determining which aspects of the CEP are relevant for which departments.

Table 8: Local Government Department Roles in CEP Implementation

Engaging Senior Management from All Departments

Consider the following GTI Advice on how to engage with senior staff.

| Who to engage | When to engage them |

|

|

| Why engage them | How to engage them and what to focus on |

|

|

Engaging Other Departments including but not limited to Planning, Transportation, GIS, Public Works and Parks and Recreation

Consider the following GTI Advice on how to engage with staff within the local government.

| Who to engage | When to engage them |

|

|

| Why engage them | How to engage them |

|

|

Engaging the Finance Department

Consider the following GTI Advice on how to engage with staff within the finance department.

| Who to engage | When to engage them |

|

|

| Why engage them | How to engage them |

|

|

Embed the CEP into Staff Job Descriptions

Once staff across the municipality are engaged, amend existing and new job descriptions to include CEP considerations.

Include tasks for all positions responsible for implementing local government plans, including department heads in the above-listed departments. While the level of responsibility and tasks will vary according to the position, consider the following language as a starting point:

“The incumbent performs a variety of routine and complex technical work … including supporting the development and implementation of the Community Energy Plan.”

Relevant Resources

- Rapport national sur la mise en œuvre du plan énergétique communautaire

- Rapport national sur les politiques soutenant la mise en œuvre du plan énergétique communautaire

- La planification énergétique communautaire : Pour l'amélioration de l’environnement, de la santé et de l’économie des collectivités

- Policies to Accelerate Community Energy Plans: An analysis of British Columbia, Ontario and the Northwest Territories

Case Study 1: CEP Renewal in the City of Yellowknife, Northwest Territories

The City of Yellowknife adopted a CEP in 2006. With a target year of 2014, Yellowknife aimed to reduce its corporate GHG emissions by 20 per cent and its community GHG emissions 6 per cent, based on 2004 levels. It budgeted $500,000 annually for energy efficiency, renewable energy conversions and public awareness. By February 2013, the City surpassed its target and the projects implemented now save the City an estimated $528,000 per year.76

One of the last steps initiated during the implementation of the CEP was the adoption of a renewal process for the plan. This renewal process included the development of a strategy for public and community stakeholder engagement to support the creation of a CEP for 2015-2025. Yellowknife has since embarked on a process where a new assessment of the Community’s GHG emissions will be completed and new targets will be established.

Case Study 6: Establishing a Committee of Council in Yellowknife, Northwest Territories

The Community Energy Planning Committee was established by City Council on September 10, 2007, following the completion of the Community Energy Plan (CEP).79 The Committee is chaired by the Mayor and includes representatives from across the Community. The primary purpose of the Committee is to assist the City of Yellowknife in an advisory capacity to ensure the CEP is implemented and evolves in an effective manner. The scope of the Committee is to report and make recommendations to City Council through the appropriate

Case Study 7: Establishing a Governance Framework for Edmonton’s Community Energy Transition Strategy, Edmonton, Alberta

Edmonton City Council formed an Energy Transition Advisory Committee.81 Committee members serve

Case Study 12: City of Yellowknife Community Energy Plan Communications Plan, Northwest Territories

The City of Yellowknife Community Energy Plan Communications Plan describes a detailed approach for engaging with the public.86 At the core of the plan, there is a recognition that in order to reduce GHG emissions across the community, Yellowknife residents and businesses must change current energy use practices. This requires a shift in awareness, attitudes and

Stratégie 6:

Stratégie 7:

Stratégie 8:

Stratégie 9:

Stratégie 10:

ANNEXES

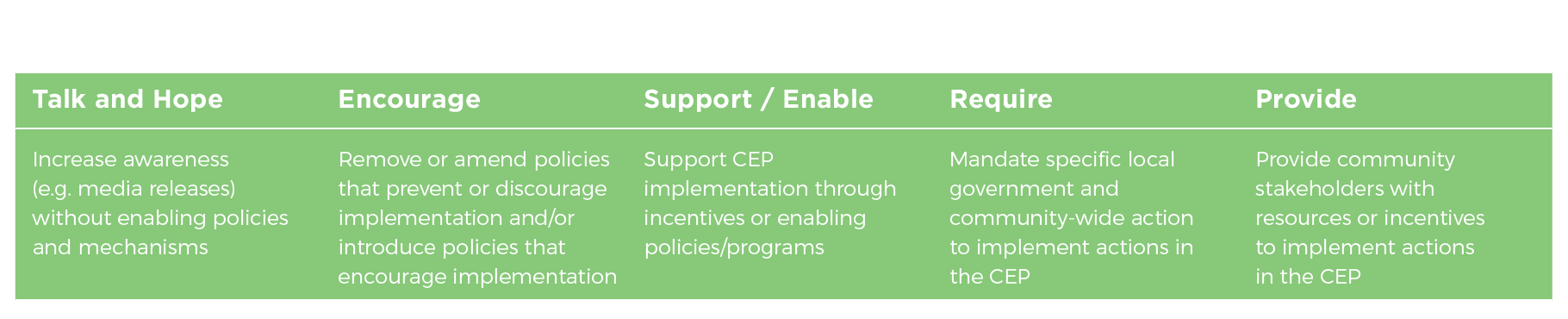

Strategy 6

Définir comment le CEP générera de la valeur pour les parties prenantes de la communauté

While CEPs are often led by local governments, they are implemented by the community. Early and meaningful collaboration and coordination with community stakeholders is critical for fostering buy-in, ownership and accountability for implementation.

Before engaging with stakeholders, it may be helpful to identify ways in which the CEP can add value to their business models. Some of the stakeholders most central to the success of the CEP include:

- Distributeurs d'électricité, de gaz naturel et d'énergie thermique

- The real estate sector (including developers, homebuilders, building owners and operators, architects, and real estate agents)

- Provincial/territorial government

- Large energy users in the industrial commercial and institutional sector

- NGOs

The value of community energy planning to each of these stakeholders is described in the following subsections.

Other stakeholders to engage include, but are not limited to:

- Local chambers of commerce

- School boards

- Fuel suppliers

- Engineering and planning consultants

- Other local governments

- Le public

- Others

Engaging Energy Distributors

Electricity, natural gas and thermal energy distributors are critical partners for CEP development and implementation as they have technical expertise in managing infrastructure and experience delivering programs and building projects.

- The business models of energy distributors are evolving. Some of the factors influencing this shift include, but are not limited to:

- The introduction of ambitious conservation targets

- The installation of smart meters in several jurisdictions and resulting data and IT management

- Increased adoption of new technologies, including distributed energy resources and alternative fuel vehicles, as well as the introduction of policies encouraging their uptake

Table 9 summarizes how a CEP can add value to the evolving business models of energy distributors.

Table 9 – The Value Proposition of Community Energy Planning to Energy Distributors

| Considerations | CEP Value |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Consider the following when engaging with the energy distributors.

| Who to engage | When to engage them |

|

|

| Why engage them | How to engage them |

|

What the CEP can provide:

What is required from distributors for the CEP:

|

|

Engaging the Real Estate Sector

Business models within the real estate sector are evolving. Some of the factors influencing this shift include, but are not limited to:

- The evolving preferences of home buyers and businesses. There is a growing mismatch between the high demand for energy efficiency buildings and homes and the supply. Similarly, there is a growing demand for compact, mixed-use neighbourhoods and communities

- Increasing concerns from building owners and operators about the growing cost of energy as a proportion of overall building operating costs

- Federal, provincial and territorial policies evolving in favour of energy efficiency, integrated land use and transportation and distributed energy resources

- Significant, untapped opportunities for integrating distributed energy resources into building design

These changes have impacts on real estate developers, building owners and operators, architects and real estate agents and while some organizations are taking the lead when it comes to community energy projects, many have yet to catch up. Table 10 summarizes some of the realities the real estate sector is facing and describes how participating in the community energy planning process can add value to their business models.

Table 10 – The Value Proposition of Community Energy Planning to the Real Estate Sector

| Real Estate Sector Factors | CEP Value |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Consider the following when engaging with the real estate sector.

| Who to engage | When to engage them |

|

|

| Why engage them | How to engage them |

|

|

Engaging Provincial and Territorial Governments

Provincial and territorial governments are essential in the community energy planning process:

- Increasingly, provincial and territorial governments and their respective agencies are placing a growing emphasis on energy and emissions.39 Community energy planning offers a platform to achieve deep energy and GHG reductions while facilitating economic growth and can directly help achieve provincial and territorial objectives

- Health care costs represent a large, and increasing portion of most provincial/territorial budgets and community energy planning can help to reduce these costs

- They also oversee policies and programs that may impact or be impacted by community energy planning.

- They may also have

technical expertise needed for CEP development and implementation - They may have energy

end use data and - Key Performance Indicator data needed to monitor implementation progress

Consider the following when engaging with provincial and territorial governments.

| Who to engage | When to engage them |

|

|

| Why engage them | How to engage them |

|

What provincial/territorial governments may need from communities:

What communities may need from provincial/territorial governments:

|

|

Engaging Non-Governmental Organizations

| Who to engage | When to engage them |

|

|

| Why engage them | How to engage them |

|

|

Engaging the Public

CEP implementation requires residents and businesses to change the way they consume energy. But when and how should the public be engaged, and what for?

- While the CEP should be undertaken with the public interest in mind, public engagement may not be needed before a CEP is developed

- Public engagement may be most effective once programs have been developed, whereby targeted educational materials and calls to action can be presented to residents and businesses

- Engagement is often most powerful when you go to the community, instead of waiting for the community to come to you. There are many tried and tested alternatives to public engagement meetings

- When communicating with the public, emphasize person benefits such as cost savings

- Use visually compelling materials such as infographics and energy maps41

- Engage youth to solicit ideas for change. Engage students to act as ambassadors for the CEP

Relevant Resources

- Rapport national sur la mise en œuvre du plan énergétique communautaire

- Rapport national sur les politiques soutenant la mise en œuvre du plan énergétique communautaire

- La planification énergétique communautaire : Pour l'amélioration de l’environnement, de la santé et de l’économie des collectivités

- Policies to Accelerate Community Energy Plans: An analysis of British Columbia, Ontario and the Northwest Territories

- Canada Green Building Council Municipal Green Building Toolkit

- Vancouver Island Real Estate Energy Efficiency Program

Case Study 2: Measuring the Widespread Economic Benefits in the City of London, Ontario

The City of London, Ontario has conducted an economic analysis to measure various economic impacts and potential benefits of implementing their Community Energy Action Plan (CEAP). The analyses, conducted in-house, demonstrate community-wide energy spending, the proportion of energy spending leaving the local economy and the potential to recirculate energy spending based on the implementation of their plan.

The approach undertaken and resources are available here:

- Energy spending analysis

- Video supporting energy spending analysis: Turning energy data into energy dollars

- The City of London has also produced infographics based on the analyses, available here

Case Study 3: Measuring Green Jobs in Durham Region, Ontario

The Region of Durham Community Climate Change Local Action Plan highlights the estimated environmental, economic and social impacts of implementation. The plan is available

Case Study 4: Measuring the Impacts of Sustainable Communities on Local Retail Sales New York City, New York

The New York City Department of Transportation created a methodology for measuring the economic impacts of improved streetscapes and active transportation infrastructure on retail sales. The study is available here: New York City Department of Transportation (December 2013). The Economic Benefits of Sustainable Streets. http://www.nyc.gov/html/dot/downloads/pdf/dot-economic-benefits-of-sustainable-streets.pdf

Case Study 5: Framing the Value Proposition, Edmonton, Alberta

The City of Edmonton, Alberta (population 812,000) adopted Edmonton’s Community Energy Transition Strategy in April 2015 and a corresponding City Policy C585 in August 2015.78 The Strategy, which represents a renewal and upgrade of their 2001 plan, was approved unanimously by City Council. Based on extensive citizen consultation, the strategy includes twelve strategic courses of action and an eight-year action plan with more than 150 tactics.

There is a lesson to be learned in how Edmonton’s Sustainable Development Department communicated the need for the strategy. First, it was framed as a risk management strategy designed to protect Edmonton’s

Case Study 6: Establishing a Committee of Council in Yellowknife, Northwest Territories

The Community Energy Planning Committee was established by City Council on September 10, 2007, following the completion of the Community Energy Plan (CEP).79 The Committee is chaired by the Mayor and includes representatives from across the Community. The primary purpose of the Committee is to assist the City of Yellowknife in an advisory capacity to ensure the CEP is implemented and evolves in an effective manner. The scope of the Committee is to report and make recommendations to City Council through the appropriate

Case Study 7: Establishing a Governance Framework for Edmonton’s Community Energy Transition Strategy, Edmonton, Alberta

Edmonton City Council formed an Energy Transition Advisory Committee.81 Committee members serve

Case Study 8: Stakeholder Engagement in the City of Kelowna, British Columbia

In 2012, the City of Kelowna adopted a Community Climate Action Plan containing 87 actions to be implemented by 2020. Of those actions, 59 were assigned to the local government and 28 were assigned to community stakeholders, including utilities, provincial government and others. In an effort to ensure that community stakeholders understood their roles in the implementation of the plan, the City of Kelowna circulated letters to the organizations responsible for implementing actions in the plan. These letters enabled the City of Kelowna to move forward on implementing actions that are not within its jurisdiction.82

Case Study 9: Stakeholder Engagement in Markham, Ontario

In 2014, the City of Markham began to develop a Municipal Energy Plan (MEP). As part of the MEP, the City created a Stakeholder Working Group.83

The desired outcome of the Stakeholder Working Group is to provide recommendations and feedback on the development of Markham’s MEP including:

- Identifying energy opportunities and solutions to increase local energy production and conservation

- Identifying synergies between industry stakeholders to implement MEP recommendations

See the Municipal Energy Plan Stakeholder Working Group Terms of Reference ici.

See the list of stakeholders participating in the MEP Stakeholder Working Group ici.

Case Study 11: Public Engagement on Community Energy in London, Ontario

The City of London, Ontario has documented public engagement efforts in a document entitled Learning from People: A Background Document for the Community Energy Action Plan: https://www.london.ca/residents/Environment/Energy/Documents/Learning_from_People.pdf

As part of the development of the Community Energy Action Plan, the City of London undertook a campaign called ReThink Energy London. The City of London held a Community Energy Strategy Workshop and the London Roundtable on the Environment and the Economy to inform the development of the Community Energy Action Plan. Community Energy Strategy Workshop included an interactive energy mapping exercise that involved 31 participants from electrical, natural gas and thermal utilities, internal departments, environmental and transportation advisory committees and provincial staff, among other stakeholders. The city’s energy map was used to help stakeholders identify energy opportunities and risks, and to generated ideas and principles for energy actions in key areas such as buildings, transportation and low carbon energy generation in the City of London. Outcomes from the workshop can be found here: https://www.london.ca/residents/Environment/Climate-Change/Documents/London_FINALSummaryofWorkshop_May11.pdf

Case Study 12: City of Yellowknife Community Energy Plan Communications Plan, Northwest Territories

The City of Yellowknife Community Energy Plan Communications Plan describes a detailed approach for engaging with the public.86 At the core of the plan, there is a recognition that in order to reduce GHG emissions across the community, Yellowknife residents and businesses must change current energy use practices. This requires a shift in awareness, attitudes and

Case Study 13: Fort Providence, Northwest Territories

In 2007 and 2008 the community of Fort Providence, Northwest Territories (population 735), in partnership with the Arctic Energy Alliance, developed an energy profile.87

The objective of this exercise was to provide the community, and key decision makers, with a snapshot of energy use in the community.

The energy profile was developed to communicate a large quantity of energy data, including energy consumption, energy end use, cost of energy, and GHG emissions. Similar to any community that looks at energy use and costs per capita, the energy profile revealed significant opportunities to conserve energy and improve efficiency within the community.

Case Study 19: Community Energy Planning Alternatives for Small Communities – Eco-Ouest

Eco-Ouest, led in partnership with CDEM, SSD, has developed a program designed to help provide expertise to smaller municipalities in Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta that face resource and capacity constraints for CEP development and implementation. Eco-Ouest has partnered with rural municipalities in each of these provinces to create energy and GHG emissions inventories and Climate Change Local Action Plans such as the inventory for the Rural Municipality of St. Clements and plans for the Rural Municipality of Saint-Laurent and Rural Municipality of Taché. CDEM also incorporates a regional perspective by comparing neighbouring communities’ energy and emissions performances and sharing successful projects and case studies.92CDEM. (n.d.). Eco-West. Retrieved from CDEM Website: http://www.cdem.com/en/sectors/green-economy-1/eco-west

Case Study 20: Yukon Energy Solutions Centre

The Yukon Energy Solutions Centre is part of the Energy branch in the Government of Yukon Department of Energy, Mines and Resources.

The Energy Solutions Centre offers community-level energy services to such as:

- Providing technical information and financial incentives to encourage the use of energy efficient appliances and heating systems at the local level

- Providing comprehensive energy planning services, including energy baseline assessments and policy reviews

- Providing training courses to build local technical capacity to implement community energy plans and projects

- Participating in outreach and public education on the health, safety, economic and environmental benefits of energy efficiency and renewable energy

To learn more about the Energy Solutions Centre visit http://www.energy.gov.yk.ca/about-the-energy-branch.html

Strategy 7

Engage Community Stakeholders and Recognize their Implementation Progress

CEPs are typically led by local government and implemented by the community. Central to the success of a CEP is effective and ongoing community stakeholder engagement. Some of the most critical stakeholders to engage in implementation include, but are not limited to:

- Distributeurs d'électricité, de gaz naturel et d'énergie thermique

- The real estate sector, including developers, homebuilders, building owners and operators, architects and real estate agenda

- Provincial and territorial government and their respective agencies

- NGOs

- Academic institutions

- School boards

- Fuel suppliers

- Chambers of commerce and local Business Improvement Areas (BIAs)

Approaches for Stakeholder Engagement

Table 11 provides a preliminary checklist of approaches for engaging with stakeholder groups. Before getting started, consider the following:

- Establish a relationship with community stakeholder as early as possible in the CEP process

- Use plain, clear language when engaging with stakeholders. If possible use terminology that community stakeholders are familiar with

- Not everyone will be supportive of the CEP. Recognize personal dynamics and focus engagement efforts on allies. With that in mind, offer ongoing opportunities to inform and engage all stakeholders

- The CEP may surface debates among stakeholders. Keep in mind that the overall aim of the CEP is to improve the overall quality of life for the community. Find ways to keep the conversation positive

- If your community does not yet have a CEP, find a way for all stakeholders to provide input in the CEP vision and energy and GHG targets

- Collaborate with community stakeholders to identify actions to include in the plan

Table 11: Approaches for Stakeholder Engagement42

| One-On-One Meetings |

When meeting stakeholders for one-on-one meetings consider the following three questions:

Click ici for a downloadable document of additional questions for consideration. |

|---|---|

| Establish A Stakeholder Committee |

|

| Workshops And Focus Groups |

|

| Ongoing Telephone And Email Correspondence |

|

| Attend Stakeholder Meetings (E.G. Association Meetings) |

|

| Charrettes |

|

| Additional Resources |

|

Segmenting Stakeholders

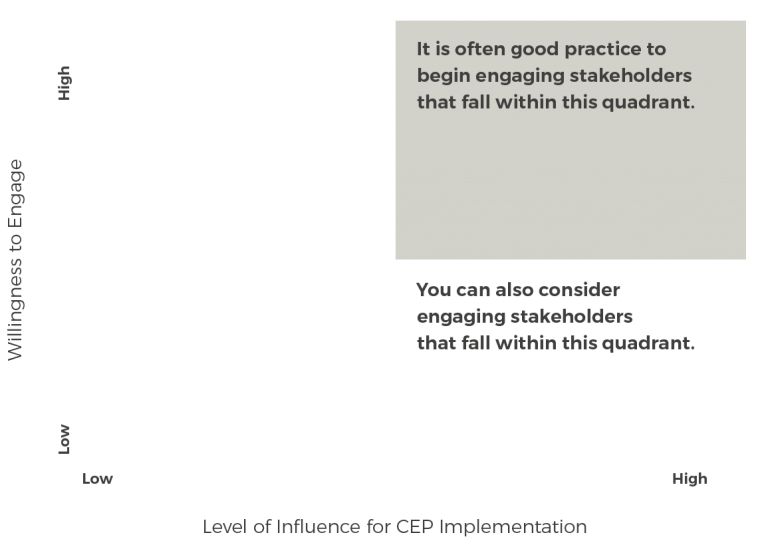

All stakeholders will have varying levels of interest in the CEP based on their core business. Consider segmenting stakeholders before you begin engaging with them.

Consider segmenting stakeholders within a matrix to determine (1) their willingness to engage and (2) their level of influence with respect to implementation. It is good practice to focus first on the stakeholders with a high influence on energy and GHG emissions. See the Stakeholder Segmentation Matrix Template in Figure 5 as an example.

Figure 5 – Stakeholder Segmentation Matrix Template

It is important to keep track of stakeholder contact information as well as a record of stakeholder input. Consider using the Tools 4 Dev Stakeholder Analysis Matrix template to keep track of stakeholders and to highlight why the CEP is of value to them.44

This matrix can help with future engagement and can also help to avoid a loss of internal corporate knowledge in the event of staff turnover or attrition.

Energy Mapping as an Engagement Tool

An energy map illustrates spatial information about energy end use in a community. It can visually identify opportunities for reducing energy use (e.g. targeting energy efficiency programs), opportunities for shifting modes of transportation (e.g. transit projects), potential sources of energy (e.g. biomass), and opportunities for distributed energy resources (e.g. district energy systems).45

Consider the following when developing an energy map:

- Before developing an energy map, consider the overall objectives of your CEP. Use the energy map

- as a strategic tool to illustrate opportunities to achieve those objectives.

- Many energy data providers may not provide parcel-level information due to privacy constraints, however parcel-level data is often not needed to illustrate energy opportunities in your community. Consider developing your map at a postal code scale. If possible, identify energy intensity by land use type or building type or by hectare or m2

- Maps should include key roads and/or buildings to help viewers orient themselves

- Consider developing a variety of maps to illustrate energy use in buildings and transportation

- Energy maps can be presented to stakeholder groups such as energy distributors, real estate developers, and the public in charrettes, stakeholder meetings, workshops and focus groups. Maps can be used to illustrate the objectives of the CEP, and to obtain input on actions to include in the CEP.

Tailor Stakeholder Engagement to Community Size and Resources

Recognize Community Stakeholder Progress when Monitoring and Reporting on Implementation

Strategy 8: Monitor and Report on CEP Implementation describes the importance of keeping track of the measurable results of the CEP on an annual basis and sharing those results with all political, staff and community stakeholders. While much of this progress is monitored by the local government, there is an opportunity to engage community stakeholders to provide input on measurable progress.

- Consider providing a formal opportunity for community stakeholders to share measurable progress

- Results can be presented in the form of ongoing Key Performance Indicators (such as the number of energy efficiency retrofits and/or the amount of kilowatt hours and gigajoules reduced)

- Or they can be presented in the form of anecdotes (such as short case studies highlighting successes)

- Meaningful engagement such as this can unlock many other opportunities to strengthen the value of the CEP.

Relevant Resources

Case Study 8: Stakeholder Engagement in the City of Kelowna, British Columbia

In 2012, the City of Kelowna adopted a Community Climate Action Plan containing 87 actions to be implemented by 2020. Of those actions, 59 were assigned to the local government and 28 were assigned to community stakeholders, including utilities, provincial government and others. In an effort to ensure that community stakeholders understood their roles in the implementation of the plan, the City of Kelowna circulated letters to the organizations responsible for implementing actions in the plan. These letters enabled the City of Kelowna to move forward on implementing actions that are not within its jurisdiction.82

Case Study 9: Stakeholder Engagement in Markham, Ontario

In 2014, the City of Markham began to develop a Municipal Energy Plan (MEP). As part of the MEP, the City created a Stakeholder Working Group.83

The desired outcome of the Stakeholder Working Group is to provide recommendations and feedback on the development of Markham’s MEP including:

- Identifying energy opportunities and solutions to increase local energy production and conservation

- Identifying synergies between industry stakeholders to implement MEP recommendations

See the Municipal Energy Plan Stakeholder Working Group Terms of Reference ici.

See the list of stakeholders participating in the MEP Stakeholder Working Group ici.

Case Study 11: Public Engagement on Community Energy in London, Ontario

The City of London, Ontario has documented public engagement efforts in a document entitled Learning from People: A Background Document for the Community Energy Action Plan: https://www.london.ca/residents/Environment/Energy/Documents/Learning_from_People.pdf

As part of the development of the Community Energy Action Plan, the City of London undertook a campaign called ReThink Energy London. The City of London held a Community Energy Strategy Workshop and the London Roundtable on the Environment and the Economy to inform the development of the Community Energy Action Plan. Community Energy Strategy Workshop included an interactive energy mapping exercise that involved 31 participants from electrical, natural gas and thermal utilities, internal departments, environmental and transportation advisory committees and provincial staff, among other stakeholders. The city’s energy map was used to help stakeholders identify energy opportunities and risks, and to generated ideas and principles for energy actions in key areas such as buildings, transportation and low carbon energy generation in the City of London. Outcomes from the workshop can be found here: https://www.london.ca/residents/Environment/Climate-Change/Documents/London_FINALSummaryofWorkshop_May11.pdf

Case Study 12: City of Yellowknife Community Energy Plan Communications Plan, Northwest Territories

The City of Yellowknife Community Energy Plan Communications Plan describes a detailed approach for engaging with the public.86 At the core of the plan, there is a recognition that in order to reduce GHG emissions across the community, Yellowknife residents and businesses must change current energy use practices. This requires a shift in awareness, attitudes and

Case Study 16: Monitoring and Reporting on Implementation Progress in the City of Guelph, Ontario

CEP reporting is coordinated annually by the Community Energy division of the Business Development and Enterprise department, and presented to the Corporate Administration, Finance & Enterprise Committee (this Committee is appointed by Council and made up of Councillors). A dashboard is used to display progress within eight key activity categories, plus a description of the status for each individual activity.

See the Guelph Community Energy Plan ici.

Case Study 17: Monitoring and Reporting on CEP Implementation in the City of London, Ontario

The City of London Community Energy Action Plan (CEAP) was adopted in 2014. Alongside the plan, the City of London developed a background document describing a methodology for monitoring and reporting on community energy use. The background document describes a methodology for developing annual energy and emissions inventories. The document describes how the City of London will also work with stakeholders to develop new Key Performance Indicators, including economic, transportation, and energy performance indicators. The results from energy and emissions inventories, and other Key Performance Indicators will be included in an annual progress report outlining implementation progress of the CEAP.90

Strategy 8

Monitor and Report on CEP Implementation

Based on research from the GTI initiative, 90

Monitoring and reporting on implementation can unlock significant opportunities to build ongoing support among elected officials, staff and community stakeholders. Precise, measurable and defensible data, when presented on an ongoing basis, can increase the overall confidence and support of senior decision makers. When the CEP is monitored on an annual basis, successes can be celebrated which can

Measuring Primary and Secondary Key Performance Indicators

CEPs typically contain primary and secondary Key Performance Indicators.

Primary Key Performance Indicators: Energy

- Communities should undertake to renew energy and GHG inventories on an annual basis

- The Federation of Canadian Municipalities offers a Framework for monitoring energy and GHG emissions. See the Guidelines for Monitoring, Reporting and Verifying Progress http://www.fcm.ca/Documents/reports/PCP/Monitoring_Reporting_and_Verification_Guidelines_EN.pdf

Secondary Key Performance Indicators: Other Key Performance Indicators

- Secondary Key Performance Indicators are typically much broader than energy and GHGs however they are strongly linked

- They often include items such as

number of home energy efficiency retrofits conducted, kilometres of bicycle lanes constructed, and tonnes of organic solid waste diverted from landfill - Secondary Key Performance Indicators should also include financial/economic indicators

- Consider the following matrix for determining KPIs

- Examples of secondary Key Performance Indicators can be found in the following CEPs:

- See Part III – Implementation Framework – in the City of Campbell River, British Columbia Community Energy and Emissions Plan: http://www.campbellriver.ca/your-city-hall/green-city/climate-action/community-energy-emissions-plan

- See Part 3 – Implementation & Monitoring in the City of Surrey, British Columbia, Community Energy and Emissions Plan: https://www.surrey.ca/files/ceep-02-02-2014.pdf

- See the indicators embedded throughout the City of Brandon, Manitoba Environmental Strategic Plan http://www.brandon.ca/images/pdf/adminReports/environmentalPlan.pdf

Table 12 illustrates the steps to consider for developing, monitoring and reporting on energy and GHG targets and other Key Performance Indicators.

Table 12: Steps and Considerations for Monitoring and Reporting CEP Implementation

| Step | Considerations |

|---|---|

| Identify Key Performance Indicators to monitor the impacts of the CEP |

|

| Determine a rigorous and consistent methodology for measuring progress |

|

| Determine the frequency of monitoring Key Performance Indicators |

|

| Determine the frequency of implementation progress reports Highlight successes! |

|

| Don’t forget to include success stories from community stakeholders |

|

Follow-up Energy and GHG Inventories in Small Communities

Annual energy and GHG inventories can be expensive to conduct and may, in some cases, illustrate only incremental changes with respect to energy end use and emissions in a community. As a result, small communities should consider developing inventories at longer intervals (e.g. bi-annually, or every five years). In the interim, communities can focus on monitoring and reporting on secondary indicators, which are often less expensive and easier to monitor, and which can still indicate implementation progress.

Insights on Measuring Implementation

GTI research has identified that there are many ways to measure CEP implementation. Some approaches include:

- Measuring reductions in community-wide energy or GHG emissions: If energy and GHGs are falling in a community, the CEP is effectively being implemented. Note that federal, provincial/territorial policies, economic transitions and other external factors often play a role in overall GHG emissions

- Measuring secondary Key Performance Indicators: The effectiveness of a CEP can be measured by the extent to which secondary Key Performance Indicators are achieved. Secondary indicators include indicators that are related to overall energy consumption (e.g. reduction in energy spending, number of jobs created, reduction in vehicle

kilometers traveled , shifts in mode splits, energy efficiency retrofits, or increased waste diversion rates) - Tracking the number of actions completed in a CEP: While this is a rudimentary approach to measuring the impacts of implementation, it can signal the extent to which local government processes are supportive of implementation

- Assessing Implementation Readiness: L' Community Energy Implementation Readiness Survey enables a community to assess the extent to which conditions are in place to support ongoing implementation

Case Study 16: Monitoring and Reporting on Implementation Progress in the City of Guelph, Ontario

CEP reporting is coordinated annually by the Community Energy division of the Business Development and Enterprise department, and presented to the Corporate Administration, Finance & Enterprise Committee (this Committee is appointed by Council and made up of Councillors). A dashboard is used to display progress within eight key activity categories, plus a description of the status for each individual activity.

See the Guelph Community Energy Plan ici.

Case Study 17: Monitoring and Reporting on CEP Implementation in the City of London, Ontario

The City of London Community Energy Action Plan (CEAP) was adopted in 2014. Alongside the plan, the City of London developed a background document describing a methodology for monitoring and reporting on community energy use. The background document describes a methodology for developing annual energy and emissions inventories. The document describes how the City of London will also work with stakeholders to develop new Key Performance Indicators, including economic, transportation, and energy performance indicators. The results from energy and emissions inventories, and other Key Performance Indicators will be included in an annual progress report outlining implementation progress of the CEAP.90

Strategy 9

Develop an Implementation Budget and Work within your Means

Effective CEP implementation will require funding to support:

- A dedicated staff person(s)

- Project capital and operations and maintenance costs

- Programmes

- Consultants

GTI Advice

When developing a budget over the expected life of the CEP consider:

- Not all actions need to be implemented immediately

- Distinguish which actions will be implemented year

over année - An implementation budget should be developed for every year of the action plan and should be updated on an annual basis

- Identify opportunities to integrate land use actions into any relevant policy/program review cycles

Fund a Dedicated Staff Person to Oversee Implementation

Many communities are concerned about the cost associated with hiring a

Consider the following approach for obtaining funding for a dedicated staff person.

| Conduct A Preliminary Funding Analysis |

|

|---|---|

| Begin Conversations With Senior Management, The Finance Department, The CAO And Council |

|

| Invite External Advisors To Speak With Senior Staff, The Finance Department, The CAO And Council |

|

Integrate CEP Actions into the Budget Process

Embedding the CEP into the budget process can draw positive attention among senior managers to the level of priority of the CEP. As a result, local government departments may be able to find ways to advance their own priorities by aligning their work plans with CEP actions (e.g. economic development and district energy, planning and higher density, transportation and bike paths, or solid waste and composting). Table 13 describes the steps to embed the CEP into the budgeting process.

Table 13: Considerations for Integrating CEP Actions into the Budgeting Process

| Consideration | Rationale |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Implement a Single Energy Project to Demonstrate the Success of the Investment