Blog

Governing Deep Decarbonization in Durham Region

Governing Deep Decarbonization in Durham Region

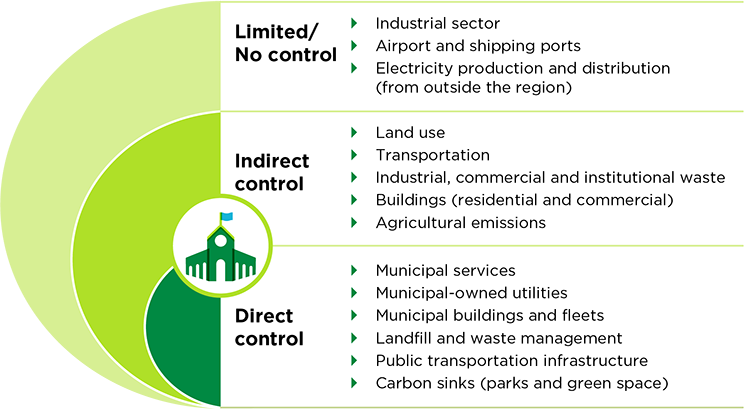

Local governments play a central role in the global response to climate change. In Canada, municipalities are estimated to have direct control or influence control over more than 50% of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions within their boundaries and are on the front lines of dealing with climate impacts to critical infrastructure and community services (e.g., public health).

Direct control includes GHG emissions from corporate assets such as buildings and vehicles, and service provision (e.g., water supply, waste, and wastewater management) which contribute between 3 to 5% of total community wide GHG emissions in Canadian municipalities.

Indirect control includes GHG emissions from the transportation and buildings sectors through land use planning, permitting, urban design, and the provision of transportation infrastructure and public transit services, among other key functions. Figure 1 below provides a conceptual framework for understanding the level of influence that local governments can have over various sources of GHG emissions.

Community Energy Planning (CEP) has emerged in Canada as a governance innovation aiming to navigate the rapid social and technological innovations associated with decarbonization. Broadly, CEP involves strategic energy planning processes considered at the community level, resulting in publicly available documents that integrate urban planning with goals such as energy efficiency in buildings, local low-carbon energy sources and alternative modes of transportation. CEP has arisen both as bottom-up processes from coalitions of local governments, citizens, and stakeholders and through top-down policies from higher levels of governments mandating or providing incentives to local governments to engage in CEP development. However, Canadian CEPs face a persistent ‘implementation gap’, with a disconnect between local government plans and the development of policies and programs to successfully implement them.

Figure 1: Municipal spheres of influence over different sources of GHG emissions (Source: FCM, 2022)

Community Energy Plan Implementation in Durham Region

Durham Regional Council approved the Durham Community Energy Plan (DCEP) in 2019, in partnership with eight local area municipalities and four energy utilities, which charted a least-cost low carbon pathway to achieving substantial GHG emissions reductions, while reducing energy costs and increasing local investment. Taking stock of progress in 2021, it became clear implementation was uneven across the six priority programs (Durham Green Standard, deep retrofits, renewable energy co-op, electric vehicle joint venture, education, and outreach, and coordinating land-use policies) in the Plan. Program areas requiring a greater degree of coordination and collaboration between many partners had the least progress.

Addressing GHG emissions in urban areas is a complex challenge requiring coordinated interventions that address changes in urban form (e.g., density and land use mix), technology adoption (e.g., electric vehicles, renewable energy systems), as well as changes to human behaviour, lifestyles, social norms, and culture. This challenge is accentuated in a two-tier regional governance context where jurisdiction over emissions from buildings, transportation, and industry—as well as GHG emissions related to the consumption of materials and waste management—is split between senior levels of government (i.e., provincial, and federal), local government (including upper and local tiers), as well as with non-governmental entities such as energy utilities (who are sometimes, but not always municipally-owned).

With this context in mind, Durham Region set out to identify a governance approach to enable greater levels of collaboration and accelerated implementation of the Durham Community Energy Plan.

Identifying a Collaborative Governance Model

As an upper-tier regional government, the Regional Municipality of Durham Region is uniquely positioned to enable a collaborative governance model to address vertical integration (i.e., multi-level governance with national and sub-national governments) and horizontal integration (i.e., collaborative governance at the community-scale with businesses, residents, and civil society groups) to help the community fully harness its potential for local climate action. This was validated through a social networking analysis that the Region conducted in partnership with academic institutions (Ontario Tech University, York University, and Trent University) that assessed how organizations in Durham Region are interacting on energy, environmental and equity issues. The Regional Municipality emerged as the most well-connected actor within the network, with the potential to connect many different sectors in a collaborative governance initiative.

Staff from Durham Region engaged a multi-stakeholder and rights holders taskforce to provide independent oversight over the process to develop a collaborative governance model. Several case studies were examined including: the Brampton Centre for Community Energy Transformation, Future Energy Oakville, Our Energy Guelph, Waterloo Region Community Energy, Bay Area Climate Change Network and Office, and the Leeds (UK) Climate Commission. An analytical framework was developed to evaluate governance options that included four categories of governance capacities: Information and Knowledge, Finance, Co-ordination and Co-operation and Institutional Capacity.

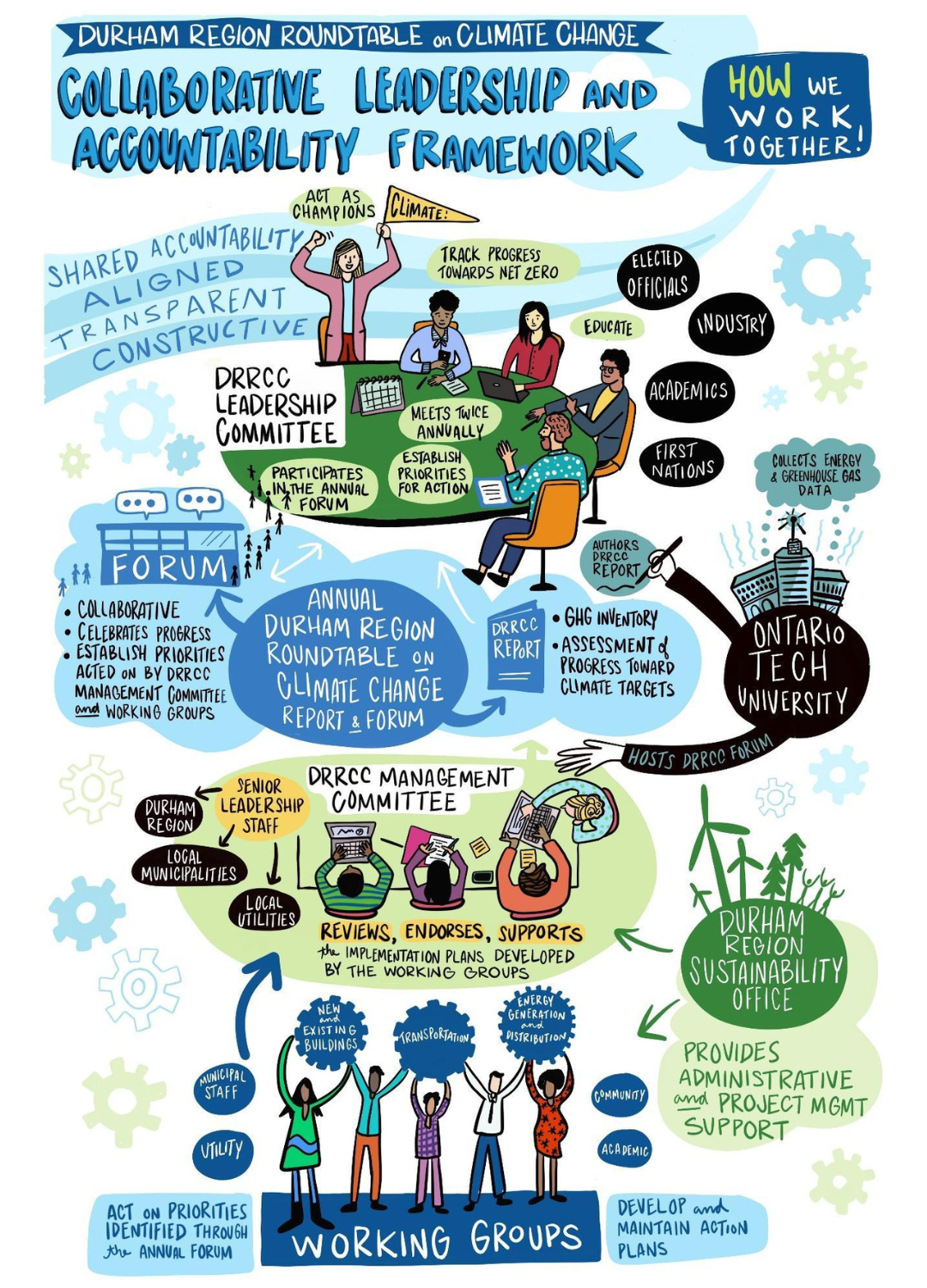

The taskforce recommended a governance approach with two primary components: 1) an independent multi-stakeholder entity coordinated and delivered through Ontario Tech University, providing strategic leadership and community oversight and 2) a range of staff-level inter-organizational working groups focused on specific topics co-ordinated and delivered through Durham Region’s CAO’s Office, providing integration, co-ordination, and recommending financing.

Durham Regional Council unanimously approved the recommendation in December 2022 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Illustration of the governance model to accelerate deep carbonization in Durham Region.

Monitoring and reporting are essential to track progress on climate action at the local level and provide an evidence base for future policy decisions. Regular information and knowledge exchange between stakeholders is critical for building capacity, as well as attracting new partners to promote decarbonization in their organizations.

Ontario Tech University will lead this independent activity for Durham Region. The two organizations will leverage their relationships with senior governments to advocate for relevant data to be more readily available to support this effort.

Finance

Significant investment is required for urban climate mitigation and adaptation, which comes in addition to funding required for core infrastructure like roads, transit systems, and water treatment plants. At the time the DCEP low carbon pathway was endorsed by Council total investment required to implement the plan was estimated to be $31 billion in investment between 2018 – 2050 (2016 dollars). That figure is most certainly higher now in 2023 given inflation and supply chain constraints in the construction industry. Financial innovation and partnerships will be essential to redress fiscal constraints.

Co-ordination and Co-operation

Municipal functions, like land use planning and transit services can influence emissions. However, that influence is bound by policy and politics at all levels of government.

Many municipalities have approached this challenge by funding independent multi-stakeholder entities that report to municipal councils, with representation from local government, utilities, Indigenous communities, civil society organizations, business associations, large employers, academic institutions, and others.

Given the co-ordinated policy and financial interventions that are required, the Region will create staff-level working groups with cross-jurisdictional membership focused on specific topics like district energy and electric vehicle infrastructure. With senior staff support, they will identify implementation priorities and drive change.

Future consideration will be given to establishing an independent entity to co-ordinate collaboration between government and non-governmental entities.

Institutional Capacities

Building shared leadership and responsibility both within the Regional Municipality, as well as with local area municipalities and agencies is critical. However, responsibility for climate planning and implementation is often “siloed” within organizational structures, creating an accountability and leadership gap. These co-ordination challenges are significant when considering areas over which local governments have only indirect influence.

The Region is developing distributed expertise on climate change throughout the organization, as well as fostering a similar approach within and between partner organizations. A decentralized approach will help to build institutional capacity in key departments for implementation. A senior Climate Leadership Steering Committee will ensure strong integration of climate action into departmental and divisional work.

Conclusion

Urban areas are a critical arena for the implementation of policies and programs to reduce GHG emissions globally, and local and regional governments are central actors in leading a co-ordinated multi-sectoral response to climate change in urban areas. Yet, local governments face challenges in fulfilling the role of leading urban climate action, including a lack of direct control over major emissions sources, fragmented jurisdiction between public agencies acting within urban areas, insufficient municipal fiscal capacity, and a limited capacity for data-driven decision-making.

In Canada, powers are constitutionally divided between the federal and provincial governments, and local governments have no constitutional status and function with authority delegated by the provinces. As such, local governments will need to consider how they will co-ordinate the local mobilization of various parties, as well as channel policy implementation through multi-level governance as part of their CEP efforts.

S'inscrire

Rejoindre la conversation!

Inscrivez-vous pour recevoir les dernières nouvelles et mises à jour sur les événements de QUEST Canada et recevez la newsletter mensuelle de QUEST Canada.